| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

Jul12

Macroeconomic imbalances - Spain

EUROPEAN ECONOMY

Occasional Papers 103

CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

2. MACROECONOMIC SITUATION AND POTENTIAL IMBALANCES

2.1. Macroeconomic scene setter

2.2. Causes and drivers of internal and external imbalances2.2.1. Housing market

2.3. Recent trends

2.2.2. Credit growth and private sector debt

2.2.3. External debt, deficits and competitiveness

2.2.4. Public debt

2.4. The adjustment capacity of the Spanish economy3. IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS OF SELECTED TOPICS

3.1. Saving-investment imbalance

3.1.1. On-going adjustment

3.2. Internal debt imbalance

3.1.2. Conclusions3.2.1.On-going adjustment

3.3. External debt

3.2.2. Assessment3.3.1. Composition and development of external indebtedness

3.4. Competitiveness and export performance

3.3.2. Assessment of the sustainability of Spain's external debt

3.3.3. Conclusions3.4.1. Price and cost competitiveness

3.5. Housing market imbalance

3.4.2. Productivity

3.4.3. The development of unit labour cost

3.4.4. Labour market and competitiveness

3.4.5. Export and import developments

3.4.6. On-going adjustment

3.4.7. Conclusions3.5.1. On-going adjustment

3.5.2. Financial sector and housing market

3.5.3. House prices developments

3.5.4. Conclusions

Executive summary and conclusions

This in-depth review takes a broad view of the Spanish economy in order to identify actual or potential imbalances and the possible macroeconomic risks which they may entail. As the main finding, this review shows the high degree of interconnection among the different imbalances characterising the Spanish economy.

With regard to the origin of the current imbalances, the existence of an abundant availability of external financing at low cost, allowed a significant increase of investment - notably in real estate - and consumption. This triggered a sharp rise in external deficits and private debt. A significant part of these financial resources was channelled into the non-tradable sector, especially the construction sector. Generous financing, combined with demographic pressures and incentives favouring housing investment, created significant housing demand, pushing up house prices and ultimately leading to a housing bubble.

The adjustment of these imbalances started in 2007 and is on-going. While the adjustment of flows (e.g. current account deficit, investment in construction, credit growth), has been relatively swift and is quite advanced in some areas, the adjustment of stocks, in particular the high levels of private and external debt, has been much more gradual and will take considerable time.

At the same time as these imbalances started to correct, significant new imbalances arose, notably in the labour market and in public finances. Indeed, unemployment soared following the downsizing of the construction sector and the cyclical adjustment in the rest of economy, which affected employment disproportionately, given the high degree of labour market duality between permanent and temporary workers and the centralised collective bargaining, which limits the sensitivity of wages to cyclical conditions. A comprehensive reform of the labour market adopted in February 2012 is aimed at addressing these issues by reducing severance pay and allowing for greater flexibility in collective bargaining. Public debt, which stood initially at a relatively low level, increased rapidly due to discretionary stimulus measures and the loss of the previous tax-rich base linked to the construction sector.

The banking sector remains burdened with sizeable exposures to the real estate and construction sectors, although additional measures were adopted recently to speed up the recognition of loan losses and to clean up balance sheets. The lending capacity of banks is constrained by a need to deleverage and re-capitalise as well as difficult access to finance. This, in turn, limits access to credit by the real economy and holds back the structural adjustment of the economy. As the adjustment proceeds, negative feedback loops between private and public sector deleveraging, compressed domestic demand, high levels of unemployment, further adjustment in the housing sector, and financial sector stability cannot be excluded. In addition, prolonged adjustment of these imbalances, due to their large size and scope, may create risks of negative spill-overs to other euro-area economies.

The main observations from this review are:

- Large accumulated private sector debt is a source of concern, especially with regard to the real estate and construction sectors. The size and scope of the necessary deleveraging implies subdued domestic demand in the medium-term with significant downside risks related to the high vulnerability of the private sector to interest rates increases associated with widening credit risk spreads. Consequently, economic growth is expected to be weak, with adverse implications for the debt repayment capacity of households and non-financial corporations. In this context, the potential risks of negative spill-overs to the financial sector are also pertinent. In addition, the reduction of private debt is a necessary condition for reducing external debt.

- The large external debt poses significant risks and needs to be brought back to a sustainable path. Large external financing needs increase the vulnerability of the Spanish economy to the changing conditions of access to finance and the interest burden. At the same time, continued build-up of unsustainable external debt positions and possible disorderly unwinding could create negative spill-overs to other euro-area economies. While the current account deficit has been reduced significantly, a shift to persistent current account surpluses will be required to restore the sustainability of the external position.

- Spain is in the process of regaining competitiveness. Spain has made important progress in terms of compensating for past losses of its price and cost competitiveness. However, a significant part of this adjustment has been due to cyclical factors, in particular the sharp reduction in employment which implied a strong improvement in measured productivity. A more structural, long-lasting, re-balancing of the economy requires that structural problems that are hampering growth and limiting competitiveness should be tackled. Spain lost some of its global market share for exports of goods and services in the past, mainly reflecting the integration of emerging export-oriented economies. But this decline was less pronounced than in the case of other euro-area countries. Moreover, Spain's export performance has been relatively resilient in the wake of the crisis. However, based on this performance, further improvements in external competitiveness and enlargement of the export base of Spanish economy are of key importance to strengthen the export-orientation of the Spanish economy. This is critical in order to mitigate the negative impact of the on-going deleveraging of the private and public sectors.

- House prices continue to fall in Spain. The bursting of the housing bubble exposed a significant oversupply of new housing, leading to an accumulation of a large stock of unsold houses. This - together with the selling pressures being exerted on banks by the new bank regulation measures with respect to their real estate repossessions - continues to exert downward pressure on house prices with potential adverse effects on private consumption and financial stability.

- •Public debt has become an emerging, rapidly-increasing, imbalance in Spain. While the share of public debt in GDP is still below the euro-area average, it is growing rapidly on the back of weak growth, rising interest payments and high budget deficits.

In this context, the in-depth review concludes that Spain is experiencing very serious macroeconomic imbalances, which are not excessive but need to be urgently addressed. In particular, macroeconomic developments, notably related to the significant level of private sector debt, the large negative external position and the financial sector, which were influenced by housing market developments, require close monitoring and urgent economic policy attention in order to avert any adverse effects on the functioning of the economy and of economic and monetary union.

The unwinding of these imbalances and the required structural adjustment of the economy depend on the flexibility of Spanish factor and product markets. The policy response of the Spanish government has been comprehensive and far-reaching. However, important challenges remain. In particular, policies aimed at increasing competitiveness and enlarging the export base of the Spanish economy, strengthening competition in product and service markets, further restructuring of the banking sector with a strong focus on troubled asset disposal, completing the adjustment of the housing sector and enhancing the scope of reforms in the labour market would support the further correction of imbalances.

On 14 February 2012, the European Commission presented its first Alert Mechanism Report (AMR), prepared in accordance with Article 3 of Regulation (EU) No. 1176/2011 on the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances. The AMR serves as an initial screening device, helping to identify Member States that warrant further in-depth analysis to determine whether imbalances exist or risk of emerging. According to Article 5 of Regulation No. 1176/2011, these country-specific "in-depth reviews" should examine the nature, origin and severity of macroeconomic developments in the Member State concerned, which constitute, or could lead to, imbalances. On the basis of this analysis, the Commission will establish whether it considers that an imbalance exists and what type of policy follow-up it will recommend to the Council.

For Spain, the AMR stressed that, even though the adjustment of imbalances is on-going, the absorption of the large stocks of internal and external debt is pending. Improvements in competitiveness are necessary to face these challenges. Moreover, correcting the disequilibrium in the housing market is essential.

Against this background, Section 2 of this review looks in greater detail into these developments covering both external and internal dimensions. This is followed by specific focus sections on the saving-investment imbalance, private sector debt, external debt, competitiveness and export performance, and housing market developments (Section 3). Section 4 presents policy considerations.

2. MACROECONOMIC SITUATION AND POTENTIAL IMBALANCES

2.1. MACROECONOMIC SCENE SETTER

The onset of the international financial and economic crisis in 2008 exposed weaknesses in the growth pattern that characterised the Spanish economy during the preceding boom period. The Spanish economy recorded a long period of strong expansion between 1996 and 2007, with average real GDP growth of 3.7% per year and job creation of over 7 million. As a result of very low and even negative real interest rates, growth was heavily skewed towards domestic demand, and in particular residential investment, which contributed to the accumulation of high domestic and external imbalances.

The economic and financial crisis hit Spain hard. Between the beginning of the crisis (Q3-2008) and the end of 2011, real GDP dropped by over 3%. Moreover, the number of people employed fell by almost 2.5 million (12% of total employment) in the same period. More than half of these lost jobs had been in the construction sector.

After some stabilisation in 2011, the economy is projected to fall back into recession in 2012. In 2011, the Spanish economy grew by 0.7%, based exclusively on resilient net exports (contributing 2.5 pps. to GDP growth). On the back of very weak domestic demand and tight credit conditions real GDP is expected to contract by 1.8% in 2012 according to the Commission Services' 2012 Spring Forecast. High unemployment, deleveraging of households and non-financial corporations, and the need for fiscal consolidation are weighing heavily on domestic demand. Indeed, the on-going correction of accumulated imbalances will affect domestic demand adversely over the forecast horizon although a gradual improvement is expected starting in 2013. The strong growth contribution of net exports is partly due to this weakness in domestic demand, implying a sharp drop in imports. At the same time, export performance in the wake of the crisis has been strong and is proving to be a major stabilising factor. As a result, the current account deficit has been narrowing and is expected to be close to balance by 2013. In addition, wage growth is expected to be moderate and, in combination with the projected continued strong growth in labour productivity, will further reduce unit labour costs. The inflation differential with the euro area is expected to be negative, leading to some improvement in price competitiveness.

2.2. CAUSES AND DRIVERS OF INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL IMBALANCES

The long period of expansion of the Spanish economy was shaped by several factors that contributed to the intensity and duration of the boom. In particular, Spain's accession to the euro area led to the disappearance of its country risk premium, reflecting the view that the risks associated with devaluations, which had occurred relatively frequently with the Spanish peseta in the ERM, were no longer relevant with a single currency. This produced two important effects. On the one hand, Spanish interest rates fell sharply |1|. On the other hand, capital inflows increased as foreign investors were more willing to take advantage of investment opportunities offered by Spain. As a result, the external financial constraint for the Spanish economy virtually disappeared.

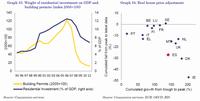

The relatively high returns offered by the Spanish economy were in turn linked to the on-going catching-up process and Spain's lower starting position in terms of per capita income. In fact, part of this inflow of financial resources was used to increase the capital intensity of the Spanish economy, with investment in equipment increasing its weight on GDP by 1.4 pps. between 1995 and 2007, twice the euro-area average. In addition, an important share of these external financial resources went to the non-tradable sector, and more specifically to construction and real estate activities.

This huge increase of external financing was, unavoidably, accompanied by an increasing current account deficit (Graphs 1 and 2). Moreover, in the case of Spain, the main part of these financial resources was absorbed by the construction sector and not by the tradable sectors, implying a limited impact on future growth.

Click to enlarge

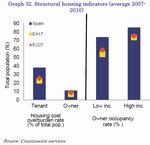

The reduced cost of capital and easier access to credit, combined with policy incentives promoting house ownership, fuelled housing demand. Indeed, the reduction of the country risk premium and high availability of foreign capital implied very low nominal interest rates (and even negative real interest rates) during some periods. Housing supply followed but only with a lag. As a result, house prices started to accelerate since 1998, registering annual increases of more than 10% up to 2006 and smaller but positive rates of growth until the second half of 2008. The emerging housing boom was underpinned by demographic factors. Population growth -both total and working age -accelerated from 1999 to 2008, and the number of households rose. This had its origin in the entrance of the 1970s baby-boom cohorts into the labour force, an increase in female labour force participation, and large immigration flows. Thus, while the immigrant population accounted for 2% of total population in 1999, its weight reached 10% by 2007. Finally, economic growth started to generate significant job creation (averaging 3.7% of growth between 1997 and 2007), further adding to the demand for housing.

The combination of low interest rates, accessible financing |2|, demographic pressure, rising house prices and the perception that these higher prices would be sustained, making house purchases appear to be a safe investment, fed a housing bubble that produced a sharp increase in housing production and prices. House prices almost tripled between 1997 and early 2008, while production of housing more than doubled from the 1995 level. Over 6.5 million new homes were built between 1996 and 2009. As a result, the weight of investment in construction reached 22% of GDP in 2006-2007, compared with 15% in 1995. This represented a significant diversion of productive resources towards the construction sector. Construction employment reached 14% of total employment in 2007, compared with 9% in the years before the expansion period.

2.2.2. Credit growth and private sector debt

The transfer of financial resources to construction sector exceeded the scale of transfer of production factors, given that the financing needs of this sector are usually higher than in the rest of the economy. Indeed, in 1995, 39% of total MFI credit to enterprises and households was related to construction and housing (loans to construction companies, real estate and loans for the purchase and renovation of dwellings). In 2007, these loans accounted for 65% of total MFI credit, after growing at an annual average rate of 22%. This expansion of credit to the construction sector was significantly helped by the easing of financing conditions.

However, it was not only the credit associated with construction that rose sharply in the period of expansion. Credit to other productive activities and to household consumption also experienced a boom, with an average growth rate of 12% between 1997 and 2007. As a result, private sector debt rose appreciably. Specifically, it reached 227% of GDP in 2010, well above the threshold of the MIP scoreboard (160%).

2.2.3. External debt, deficits and competitiveness

The level of total accumulated foreign debt reached 164% of GDP in 2010. However, external financing was not only used for internal operations in Spain, but also to finance investment by Spanish companies abroad. Consequently, the net international investment position (-89.5% in 2010) is lower than the volume of total external debt, but still above the scoreboard threshold of -35% (Graph 3).

Click to enlarge

The inflow of huge external financial resources, which financed consumption and to an even greater extent investment (Graph 4), resulted in the appearance of sustained and increasing external deficits. Indeed, the gap between imports and exports rose, as the strength of domestic demand pushed up imports.

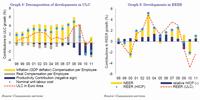

At the same time, foreign capital inflows and the induced domestic demand boom pushed up wages and prices, contributing to a steady deterioration in the cost and price competitiveness of the Spanish economy. The gap between wage growth (3.2% on average in the period 1996-2007) and a historically subdued productivity growth (0.4% on average in the period 1996-2007) widened and unit labour costs rose significantly (2.8% on average over the same period and more than double the euro-area average) (Graph 5). Thus, in the period 1999-2009, the REER (based on ULC) vis-a-vis IC35 appreciated by 16%, which imposed a drag on the expansion of Spanish exports. It addition, it was also an indication of a loss of competitiveness of Spanish products in the domestic market (Graph 6).

Click to enlarge

Public debt can be considered an emerging but also a rapidly increasing imbalance in Spain. It has only emerged in the last couple of years as, partially, a mirror image and a consequence of the on-going adjustment in the private sector. The other source of this rising debt is the misalignment between public expenditures and public revenues, which, during the housing boom, were based on a tax-rich base. The debt-to-GDP ratio was barely above the MIP scoreboard target of 60% in 2010, but it reached 68.5% already in 2011. While its level is still relatively low compared to other euro-area countries, the fast pace of its deterioration is a source of concern. In absolute terms, public debt has increased by about 70% since 2008 and is expected to increase further reaching close to 90% of GDP by 2013 despite on-going fiscal consolidation. One of the important effects of increasing fiscal deficits and growing public debt has been a significant increase of Spanish risk premia. However, this higher financing cost is not only limited to sovereign debt, but also affects the cost of financing of Spanish MFIs and ultimately of non-financial private sector.

The extended housing and credit booms between 1997 and mid-2008 were associated with the accumulation of various imbalances including: excessive weight of the construction sector, excessive credit growth to the private sector, sustained loss of competitiveness and, finally, excessive reliance on external financing. The turning point had already been reached in late-2006 and early-2007. Interest rates started increasing in 2006, which, combined with the already high degree of household indebtedness, led to an easing of demand for housing and credit. By that time, the affordability ratio associated with buying a house had increased to 46% of household disposable income (compared to 28% in 1999). This also affected private consumption, which started to decelerate in 2007. As the economy still grew by close to 4% in 2007, the adjustment was relatively soft. However, the economic and financial crises in 2008 triggered a much sharper correction. While some imbalances adjusted very rapidly, others were more persistent. Moreover, additional imbalances started to emerge in the wake of the crisis, notably in the labour market and with regards to public finances.

The adjustment in the construction sector has been very rapid since 2008. Over the period 2008-2011, the share of construction investment in total GDP fell below the pre-boom level (14%). Employment in the construction sector fell by around 1.4 million over the same period and the weight of construction in employment reached its lowest level since 1976. House prices have fallen by 29% (in real terms) since their peak and this decline gathered pace in the last quarter of 2011 when house prices registered a reduction of 11% (y-o-y). The drop in housing demand, which occurred from 2008 onwards along with the tightening of credit conditions, contributed to a contraction of credit throughout 2011. Finally, the current account deficit decreased from 9.6% of GDP in 2007 to 3.4% in 2011.

While the correction of imbalances in terms of flows has therefore progressed in the wake of the crisis, the adjustment of imbalances in terms of stocks has been much less. The stock of credit to the private sector has decreased by 10 pps. of GDP, but remains very high (213% of GDP). The net international investment position has continued to deteriorate in line with sustained current account deficits, reaching -92% of GDP in the third quarter of 2011 and well above the -35% scoreboard threshold value. Putting external debt on a downward path would require a shift to structural external surpluses for a prolonged period, based on further improvements in the competitive position of the Spanish economy. Since the beginning of the crisis, the loss in competitiveness during the expansion period has only partly been corrected.

Finally, the economic crisis has brought to the fore imbalances in the housing market. The fall in housing demand exposed a significant oversupply of new housing, the volume of which is estimated up to one million units. This reduces the availability of significant financial resources for alternative productive activities.

2.4. THE ADJUSTMENT CAPACITY OF THE SPANISH ECONOMY

The capacity of the Spanish economy to undergo the necessary adjustment will depend on the smooth functioning of its factor and product markets, in particular the labour market. Indeed, unemployment has emerged as a very significant imbalance of the Spanish economy as it rapidly increased following the downsizing of the construction sector. Up to now, labour market rigidities, including wage setting mechanisms -which restricted the responsiveness of wages to economic conditions - and a high degree of labour market duality, have been aggravating the crisis-induced surge in unemployment. The recently-adopted labour market reform aims to address these challenges. However, the employability of the large number of low-skilled workers made redundant in the construction sector still poses a challenge. The banking sector remains burdened with sizeable exposures to the real estate and construction sector, even though additional measures were adopted recently to speed up the recognition of losses and to clean up balance sheets. The lending capacity of banks is constrained by a need for further re-capitalisation and difficult access to finance. This limits access to credit by the real economy and holds back the structural adjustment of the economy. In addition, certain product market inefficiencies, including weak competition in professional services and the heterogeneity of administrative rules among regions, also hamper the re-allocation of resources.

The adjustment of large external and internal imbalances built up in the years prior to the crisis is propelling the Spanish economy through a period of subdued economic growth combined with very high unemployment. These developments, in turn, slow down the on-going deleveraging process and the adjustment in the housing sector. They also have adverse effects on the financial sector, thus reducing the flow of credit and putting an additional brake on economic growth. Moreover, due to the size and nature of the accumulated imbalances, Spain is vulnerable to external shocks, such as rises in interest rates. Such external shocks may have adverse effects on the on-going adjustment. In sum, as the adjustment of the economy progresses, negative feedback loops between private and public sector deleveraging, compressed domestic demand, high levels of unemployment, further adjustment in the housing sector, financial sector stability and credit availability cannot be excluded.

These imbalances may create negative spillovers to other euro-area economies. These spillovers can be transmitted through several channels, with trade and financial channels being the most important. Empirical evidence shows |3| that positive growth spillovers from Spain were significant for other large euro-area economies, including Germany, France, and Italy. However, following the burst of the property bubble, private sector deleveraging is depressing Spain's domestic demand and, thus, generating negative spill-overs.

Financial channels of transmission of shocks have gained prominence in the recent years with increasing financial integration. In the case of Spain, two possible financial channels could be identified. First, negative spillovers of Spain could be transmitted through the sovereign debt market. In particular, developments of Spanish sovereign bonds could impact on other euro-area sovereigns due to their increased correlation over time (see Box 2 for a more detailed discussion). In addition, countries characterized by a large exposure of their banking sector to Spain (such as Germany and France) may be more vulnerable to potential negative spillovers from Spain.

3. IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS OF SELECTED TOPICS

The previous section gave a general overview of the different imbalances in the Spanish economy, highlighting their interconnections. This section provides further, more in-depth analysis of the individual imbalances.

3.1. SAVING-INVESTMENT IMBALANCE

Massive private capital inflows into Spain for an extended period of time before and after euro-area accession are key to understanding the emergence of large internal and external imbalances. Initially, this external shock provided a boost to economic growth. Throughout the boom years, abundant and cheap financing led to an expansion in corporate and household (mainly residential) investment as well as household consumption. This, in turn, resulted in the emergence of recurrent and increasing current account deficits. Indeed, the gap between imports and exports increased, driven by buoyant domestic demand (see Section 3.4 on competitiveness and export performance for more details).

Households' savings and investment were in balance in the early 2000s, but the household investment increased significantly over time while their savings rate remained rather stable, leading to a widening of the saving-investment gap, which became particularly acute during the period 2004-2007 (Graph 8). The main factors driving the buoyant households' investment, in particular housing investment, included low interest rates and easy financing on the one hand and rising employment and wages feeding into increases of households' income and wealth, on the other hand. Sustained high demand for housing that lasted for a decade generated a seemingly never-ending upward trend for house prices, creating an impression of a virtually safe investment that kept feeding back into further demand. In addition, policy factors have also played a role. In particular, tax system favouring home ownership over renting (i.e. deductibility of mortgage interest payments), provided additional incentives for house purchases (see Section 3.5 on housing market imbalance for more details).

Click to enlarge

The situation was even more pronounced for non-financial corporations, with the gap between their saving and investment rates widening markedly, with investment being twice the size of saving in 20052008, both due to significantly higher investment but also due to lower savings rate (Graph 9). Most of the imbalance between savings and investment, as in the case of households, was driven by a significant increase of residential investment. Indeed, its share in total corporate investment increased by almost 10 pps. in 2000-2007 (Graph 10). In addition, as part of the catching-up process, the capital intensity of the Spanish economy increased. Indeed, the weight of investment in equipment on GDP increased by 1.4 percentage points between 1995 and 2007, twice the euro-area average. The main factors driving the rapid increase in corporate investment were the decline of risk premium and the optimistic macro-economic outlook for the Spanish economy, on the back of a long expansion period. However, the imbalance between savings and investment was also due to a reduction of savings. Indeed, the period characterized by the highest ratios of investment on GDP (2006-2007) was also the period with the lowest ratios of savings on GDP. Higher direct taxes as well as higher property incomes payments (mostly dividends) reduced gross disposable income of NFCs in those years, thus, reducing their capacity to save.

As a result of buoyant private investment in excess of savings, both household and non-financial corporation debt with Spanish financial institutions soared. This debt was, in turn, largely financed by savings from abroad, thus increasing the vulnerability of the Spanish economy to external financing conditions. As these conditions deteriorated suddenly, a rapid adjustment was prompted. By 2011, both the non-financial corporations and households ran a net lending position equivalent to around 1 and 2% of GDP, respectively (Graphs 8 and 9). Looking ahead, according to the Commission Services' 2012 Spring Forecast, both households and non-financial corporations are expected to remain net lenders over the forecast horizon (2012-2013).

Click to enlarge

While the household sector had adjusted already in 2008, the adjustment in the non-financial corporations took place only in 2010. This two year lag is mostly explained by the length of the cycle of the residential construction. Most of the adjustment so far occurred through investment, in particular construction investment, which fell by around 8 pps. from its peak in 2006 to 14% of GDP in 2011. Adjustment in terms of savings rate of households seems somewhat puzzling. After the initial jump of savings rate in 2009 to around 19% (a clear sign of initial overshooting), it has since declined to its long-run historical level of around 11%. Instead, given the large deleveraging needs of households faced with a large stock of accumulated debt, one would expect the savings rate to remain at an elevated level in the medium-term. However, the fall back to previous levels could be due to the fact that the most indebted households are also the ones with lowest levels of income (see Section 3.2 on internal debt for more details) and, thus, they may be unable to increase their savings significantly.

Public sector developments have mirror-imaged those in the private sector. The general government net borrowing position increased in the boom years (with investment less than saving), thus offsetting to some extent the debt accumulation in the private sector (Graph 11). The combination of a steady appreciation of the real effective exchange rate, the reduction of the risk premia and the increase in population in Spain was supportive of a demand-based growth model, highly rich in taxes. According to Martinez-Mongay et al. (2007), about 75% of the increase in tax revenues observed between 1995 and 2006 could have been transitory in nature. Booming domestic economy provided a steady stream of government revenues, recording a particularly steep increase in the tax revenues related to the housing market and private consumption (such as VAT but also corporate taxes). However, during the boom period, the government expenditures also increased significantly, and, as a result the government savings increased at a slower pace than the growth of its revenues (Graph 12). Indeed, as demonstrated by recent developments in public finance, the net lending position of the government proved insufficient to accommodate the disappearance of the extraordinary revenues on which this position was based. As a result, the government balance deteriorated rapidly from 2008 onwards as the government stepped in to support the domestic demand and economic growth in the context of significant private sector deleveraging. That led to the emergence of large government deficits and has significantly increased the public debt level. Despite the on-going fiscal consolidation, public debt is expected to further increase and reach close to 90% of GDP by 2013, according to the Commission Services' 2012 Spring Forecast (see also Section 2.1 of the Commission staff working document: Assessment of the 2012 national reform programme and stability programme for Spain (SWD 2012).. One of the important effects of increasing fiscal deficits and growing public debt has been a significant increase in Spanish risk premia demonstrated by a widening of the spread between Spanish and German government bond yields. This increasing risk premia may also impact the real economy, mostly through the financial sector (i.e. lending conditions for households and non-financial corporations).

Increasing reliance on external financing to cover the large saving-investment gap has increased the vulnerability of the Spanish economy, in particular to external financing conditions and the interest rate changes. Indeed, this vulnerability has been illustrated by the recent episodes of large private capital outflows, which may be characterised as sudden stops (see Section 3.3.2 on external debt sustainability for more details). While the adjustment is on-going with both households and non-financial corporations moving into a net lender position, the speed of the adjustment of stocks has been rather slow. In that respect, policy challenges include increasing the savings rate and reducing some of the existing incentives for investment in the residential sector. Addressing these challenges would facilitate further rebalancing.

Click to enlarge

High levels of private sector debt may have significant and negative consequences for the domestic economy, especially linked to the greater sensitivity to changes in cyclical conditions, inflation and interest rates. In addition, a high degree of indebtedness may adversely affect growth and financial stability. In the case of the Spanish economy, private sector debt stood at 227% of GDP in 2010 compared to the MIP indicator threshold of 160%. This high stock of private debt is the result of previous high growth rates of credit during the boom period (Graph 13). According to the latest data (2011 Q4), loans to the private sector have been falling by 3.4% and private sector debt has come down to 213% of GDP.

High debt implies a high exposure of borrowers to changes in the financing conditions given that a majority of mortgages in Spain have variable interest. In the case of households, interest payments alone accounted for 2.9% of gross disposable income in 2011, but reached more than 5.3% in 2008, when interest rates rose. For corporations, 7.4% of their gross value added went to net interests payments in 2011, rising to 11.6% in 2008 (Graph 14). Consequently, for both households and non-financial corporations, the high level of debt may impose an important drag on consumption and profitability. In addition, to the extent that this high level of debt feeds into a deterioration of the financial situation of households and non-financial corporations, the stability of the financial sector could be threatened.

The high level of private debt was fuelled by both supply and demand factors. On the supply side, euro-area accession by Spain led to a reduction of the Spanish risk premium, leading to a prolonged period of low interest rates and easy access to finance. On the demand side, the long period of low interest rates paved the way for higher economic growth and, more importantly, triggered a housing boom.

As a result of the housing boom, private debt rose significantly. Construction and residential investment, in particular, are activities which use financial resources more intensively than the rest of economy. For households, bank loans grew by 18% on average during the period 1997-2007, 78% of the growth of loans came from house purchases. For corporations, bank lending increased by 16% on average over the same period, while corporations linked to construction and real estate activities accounted for half of growth of total credit to non-financial corporations.

Click to enlarge

Slightly more than one third of total outstanding private debt is held by households (amounting to 82% of GDP). As problematic as the headline household indebtedness is, the fact that more than 90% of this debt consists of mortgages, almost exclusively with variable interest rates, mainly linked to the Euribor. Hence, more than a third of total debt is long-term debt, with maturity periods of over 20 or 30 years, and very sensitive to variations in the Euribor. Corporate debt stands at 135% of GDP. A large share is concentrated in construction and real estate (43% of total debt of non-financial corporations). However, these loans contribute disproportionately to the increase in doubtful credits: according to the latest data (February 2012), over 70% of total doubtful credits are linked to real estate and construction activities.

The adjustment of the large stock of accumulated private sector debt has started and is on-going. However, further deleveraging is likely to take several years.

Households

Household indebtedness, measured as a share of financial assets, has fallen by around 5% from its peak (2009 Q1) |4|. Already in 2008, households moved to a small net lending position (amounting to around 1% of GDP) as they increased their savings and reduced investment (Graph 8). Since then, they have continued reducing their investment, which fell to below 6% of GDP in 2011 (compared to a peak of almost 10% of GDP in 2006). At the same time, the savings rate is now at its long-term historical average level of around 11% (see Section 3.1 on saving-investment imbalance for more details). All in all, the pace of adjustment up to now has been rather slow (below 2 pps. per year) despite its large size. In 2011 Q3, indebtedness stood at 133% of gross disposable income, compared to 80% in 2001.

Deleveraging of the household sector may come from three different sources.

- First, deleveraging of households could happen through an increase of defaults. Currently, doubtful asset ratio of mortgage loans is relatively low, around 3%. However, in the current macroeconomic situation, where additional destruction of employment is expected at least in the short-term, the number of defaults may increase. This event has a high probability of occurrence if the distribution of households' debt by income level is considered. Indeed, according to the Household Financial Survey (HFS) 2008 |5|, households with low incomes (below the 20th percentile) were indebted to the tune of 140% of their income (Graph 15). This group of households is particularly exposed to increases in interest rates. Estimates based on the HFS for 2005 |6| suggest that if interest rates were to rise by 300 basis points, the share of households in the lowest percentile, whose financial burden is above 40% of their income, would increase from 31% to 37%.

- A second way for reducing households' indebtedness is through significant reduction of new credit. However, in order to reduce the huge stock of unsold new dwellings new financing to households will be necessary.

- Finally, households could also deleverage through an advance repayments of current mortgages. However, this option is not likely to result in a quick reduction of indebtedness. Indeed, in the current situation, there is little incentive for households to advance the repayment of their mortgages. The interest rates are relatively low, which is significant given that 99% of total mortgages have variable interest rates linked to Euribor |7|. Furthermore, repayments in advance of the term of the mortgage imply a penalty in terms of commission to be paid by households and would reduce (income) tax deductions in subsequent years. Finally, early repayment by the households with corresponding (liquid) assets would not reduce the economic risk for the banking sector as these are exactly the households that are 'safe', i.e. can afford their debt.

A significant increase in households' debt was driven to a large extent by the residential investment. As consequence, households have accumulated some wealth in terms of real estate assets. Indeed, 86% of their total net wealth is related to housing while the remaining 14% constitutes financial wealth (Graph 16). This can be considered as a mitigating factor given that households' liabilities are just 15% of their total wealth. Thus, even though the size of the accumulated debt is large, it appears manageable given a high level of households' solvency. On the other hand, this wealth depends on the development of house prices. Thus, a further significant fall in house prices would reduce the households' wealth.

Non-financial corporations

The deleveraging process of corporations is on-going, albeit at a relatively slow pace. Spanish NFCs are on average more indebted than the euro-area average. In 2010, the debt of Spanish NFCs amounted to around 141.6% of GDP, compared to 99.4% for the euro-area NFCs. Most of the adjustment took place in the corporations linked to the construction and real estate activities. Overall, the corporate debt-to-GDP ratio decreased by around 7 pps. between 2010 Q2 and 2011 Q4, with firms related to construction and real estate activities accounting for over 90% of this adjustment (6.7 pps. of GDP). Nonetheless, firms in this sector remain highly indebted: their current level of indebtedness is 2.4 times the corresponding level in 2000, compared to 1.5 times the level of 2000 for firms in other sectors |8|. Thus, the bulk of remaining adjustment will need to take place in firms linked to the construction and real estate activities following the pattern observed so far.

Click to enlarge

As in the case of households, the period of adjustment is expected to be long also in the corporate sector: evidence based on international experience suggests a range of time between 5 and 10 years (Aspachs-Bracons et al. (2011)). The usual process of adjustment, according to Ruscher and Wolff (2012), is through a reduction of liabilities, but also by increasing liquid assets. The funds required to change the relation between liabilities and assets would come from higher corporate savings and lower corporate investment. In the absence of higher gross value-added (which will be difficult to obtain in a period when investment is being curtailed), higher savings are achievable through lower labour costs or lower dividend payments. The implications of such a projected development of savings and investment are significant. According to the economic theory and empirical evidence, in the short term, internal demand is adversely affected by lower investment on the part of firms and lower consumption stemming from the reduced gross disposable income of households in the wake of lower compensation of employees. In the medium term, the lower level of corporate investment weighs on economic growth, thus prolonging the adjustment.

The process of adjustment process is underway, although the pace of the correction is slow and, given the size of the imbalances, the length of the adjustment is likely to be long. Indeed, non-financial corporations have increased their savings rate (to 13% of GDP compared to below 6% in 2007) and, more importantly, significantly reduced their investment (to around 12% of GDP compared to almost 17% in 2007), which allowed them to reach a net lending position in 2011 (0.8% of GDP), for the first time since 2003 (Graph 9).

The size and scope of the necessary adjustment implies subdued domestic demand in the medium-term with significant downside risks related to the high vulnerability of private sector to interest rates increases. Consequently, economic growth is expected to be weak, with adverse implications for the debt repayment capacity of households and non-financial corporations. In this context, there are potential risks of negative spillover effects to the stability of financial sector. Additionally, the reduction of private debt is a necessary condition for reducing external debt.

The pace of adjustment depends on several factors: first, the evolution of GDP itself; second, the financing capacity of households and non-financial corporations; and, third, the channelling of new financial resources towards reducing liabilities or increasing financial assets. Graph 17 illustrates different adjustment paths for private debt. Nominal GDP is assumed to grow at the potential real output growth rate projected by Commission services augmented by an increase in prices of around 2% every year. With regard to the evolution of liabilities of private sector, three scenarios are considered: a) financial liabilities remain constant, in nominal terms, during the whole period; b) financial liabilities shrink at the same pace as in 2011 Q3 (-3.1%); c) the net lending position of households and non-financial corporations remains constant over the whole period in terms of GDP, and equal to the last observed value, namely 4.5% of GDP in 2011 Q3, and all these resources are used to reduce financial liabilities.

If financial liabilities were to be maintained at their value in 2011 Q3 for subsequent years, the indebtedness ratio would not reach the scoreboard threshold until 2021, i.e. ten years later. Furthermore, the second and third scenarios yield similar paths, reaching the threshold within one year of each other. In the third scenario (the net lending position stays constant as a share of GDP over subsequent years), the scoreboard threshold would be reached in 2017, i.e. six years later. However, in order to assess this result properly, it should be noted that the underlying assumption on the evolution of net lending capacity is favourable. Indeed, the current net lending capacity, 4.5 pps. of GDP, prevails in a context of very low investment rates by households and corporations, a low level of household consumption and low profit distribution (i.e. dividends) of corporations.

Click to enlarge

The long period of economic boom of the Spanish economy was accompanied by an increasing current account deficit, the three-year average of which reached 6.5% of GDP in the 2010 against the MIP scoreboard threshold of 4%. As a consequence, the net international investment position (NIIP) has been deteriorating: it registered -89.5% in 2010, thus substantially in excess of the MIP scoreboard threshold of -35%. This large external imbalance represents a significant vulnerability for the Spanish economy in terms of both potential financing problems and the interest burden.

3.3.1. Composition and development of external indebtedness

Massive private capital inflows into Spain for an extended period of time following euro-area accession are key to understanding the emergence of large internal as well as external imbalances. On the external side, such capital flows helped to accommodate the sustained and increasing current account deficits. The current account position of a country can be viewed in two alternative ways, either as the sum of the net trade balance and net income from abroad (external dimension) or as the difference between domestic savings and investment (internal dimension). From the internal point of view, persistent current account deficits were driven by an excess of investment, especially housing investment, whereas domestic savings remained rather stable (see Section 3.1 on saving-investment imbalance for more details).

From the external viewpoint, the large current account deficits in the boom years were mainly driven by trade deficits in goods arising from dynamic growth of imports, while the growth of exports remained relatively stable. The increasing import penetration of the domestic market was supported by a buoyant domestic demand. In addition, large capital inflows led to an internal appreciation, which, in the absence of a national currency, manifested itself in an increase of prices and wages. This resulted in a persistent positive differential between domestic and import price inflation, thus, reducing Spain's price competitiveness (for more details see Section 3.4 on the competitiveness and export performance). Since 2007, the trade deficit has been substantially corrected by a significant rise in exports of goods and services and marked decline of imports, thus bringing the trade balance close to equilibrium (Graph 2).

In addition to its significant size, the composition of Spain's NIIP further increases the vulnerability of Spanish economy to external shocks (see Graph 3 on the composition of NID? and Graph 18 on the financing of the external deficit). Indeed, external liabilities are concentrated in portfolio investment (both equity and debt) and "other" investment (accounting for 67% of total external liabilities). With regard to portfolio investment, Spain has a negative position in debt (mostly due to liabilities related to bonds), while its equity position improved sharply in the last few years and turned positive in 2010. In addition, the large negative position in "other" investment arises mainly from bank loans. The high weight of these financial instruments increases the vulnerability of the economy to external shocks as they are more volatile and sensitive to changes in the investor confidence. Furthermore, loans and bonds are non-state-contingent (i.e. they have to be serviced whatever the economic situation of the debtor) unlike equity (i.e. dividends are paid only if the economic situation of the "debtor" allows it). Finally, the large weight of external debt implies a significant burden in terms of interest payments. The high degree of vulnerability of Spain's external position is also illustrated by the so-called 'solvency ratio', which is the ratio of assets held abroad to foreign liabilities (excluding direct investments in both cases). This ratio halved from around 0.8 in the early 1990s to about 0.4 at present, indicating that Spain could cover only 40% of its external liabilities in case of the sudden stop in external financing.

Click to enlarge

In terms of maturity, gross external debt (GED) held by non-financial actors is almost exclusively long-term. Total GED amounted to around 165% of GDP in Spain in end-2011. Short term debt (mostly currency and deposits) amounted to about 56% of Spain's GDP, almost exclusively concentrated in the financial system (including banks and the central bank).

The vulnerability of Spain's external position has been highlighted by recent episodes of large private capital outflows. Capital flows in the euro area can be decomposed into private capital flows and other/public flows (including Eurosystem financing). According to S. Merler and J. Pisani-Ferry (2012), Spain experienced two episodes of private capital outflows - in spring 2010 and summer 2011 -, which could qualify as sudden stops. Since these private capital outflows were compensated by equally large public capital inflows, the sudden stops are not evident from the official balance of payment statistics.

Moreover, the composition of Spain's foreign asset and liability portfolios also has implications in terms of valuation effects (Graph 19). Spain suffered from large negative valuation effects in the period 2001-2007, which contributed to a rapid deterioration of Spain's NIIP (defined as the sum of the cumulative current account deficits and valuation effect). The negative valuation effect, estimated to be around 25% of GDP (Goldman Sachs (2011)), can be decomposed further into an exchange rate effect and a price effect. Since Spain has maintained a net asset position in foreign currency, any euro appreciation generates negative valuation effects. In addition, Spain's past large negative net equity position has resulted in additional negative valuation effects during periods when equity prices were rising. In turn, since 2007, the valuation effects have been mostly positive, and are estimated at between 10-15% of GDP. Hence, in the case of Spain, the valuation effect has played a stabilising role since it turned negative in 'good' times and positive in 'bad' times. However, due to some changes in the composition of the foreign portfolio (in particular, the shift to a net equity position), valuation effects may be more limited in the future.

3.3.2. Assessment of the sustainability of Spain's external debt

The correction of the external imbalances started in 2008 with the burst of the housing and credit booms in the wake of the on-going crisis. The current account deficit has been shrinking in line with a strong decline in imports (mostly due to a very weak domestic demand) and a strong export performance (for more details see Section 3.4 on the competitiveness and export performance). Indeed, according to the latest available data, the current account deficit declined to 3.4% of GDP in 2011 and this downward trend is expected to continue in the medium-term. According to the Commission Services' Spring Forecast, current account will be close to balance by 2013.

In order to better understand the likely persistence of this downward trend, it is important to assess how much of this adjustment has been due to structural changes and how much is driven by purely cyclical developments. One important structural change is the downsizing of the housing and construction sector, which also has significant implications for the trade balance. Indeed, construction activity generally contributes to a trade deficit due to the associated imports of foreign goods; both construction materials and household equipment. Furthermore, construction sector does not export. Considering the direct and indirect import content of construction production, the downsizing of this sector would explain around one-sixth of the adjustment of external deficit (6 pps. of GDP between 2007 and 2011) |9|. Thus, so far, cyclical factors seem to have played a greater role in the adjustment of the trade deficit. In particular, the rapid decline in imports was caused mainly by weak domestic demand rather than by a structural shift of domestic demand away from imported goods and services. Also, the observed improvement in average productivity has been largely cyclical in nature to the extent it was driven by a steep fall in employment.

The key question concerns the size of the current account adjustment that will be required to improve the sustainability of Spain's external position. As a minimum, one needs to consider the size of the current account adjustment necessary to stabilise NIIP-to-GDP ratio. In case of Spain, it can be argued that the current ratio of NIIP to GDP - around -90% of GDP - is excessive and merely stabilising this at current levels will not be sufficient to secure market financing. Accordingly, the pertinent question is what should be the size of the current account adjustment to bring the NIIP-to-GDP ratio to the -35% of GDP threshold included in the MIP scoreboard.

According to the Commission services' estimates, assuming 3.4% nominal growth in Spain, a current account deficit of 3% of GDP would stabilize the NIIP at the current level. In order to reduce the NIIP position to the MIP threshold of -35% of GDP by 2022, under a baseline scenario, Spain would have to run an average current account surplus of 2.9% of GDP or 5.4% if the income balance is excluded (the income balance consists mainly of interest income and will remain negative in Spain's case owing to the negative NIIP - see Table 1. If a more gradual adjustment path is considered (i.e. reducing NIIP to -50% of GDP by 2022), the required CA surplus declines to 1.3 and 4.1, respectively. In addition, the range of estimates increases when more negative assumptions regarding the nominal growth and interest rates are considered |10|. According to Commission services' estimates |11|, despite a significant adjustment since 2007, Spanish REER appears still somewhat overvalued with respect to the 'equilibrium' REER level that would be needed to equalise the underlying current account with the current account norm.

According to the IMF estimates, Spain would need to maintain a balanced current account in order to reduce its NIIP to -45% of GDP by 2031 (implied REER depreciation is around 18%). Alternative estimates from Goldman Sachs, over a similar 20-year horizon, point to a possible impact resulting from the valuation effects. In order to achieve a NIIP of -50% of GDP, assuming an average 3% nominal GDP growth and without considering the valuation effects, the necessary adjustment would require a sustained balanced current account (as in the IMF estimates). However, under the same assumptions but including valuation effects, the required adjustment is much larger and would require a persistent current account surplus of around 4.5% of GDP over the whole period. The corresponding price adjustment (REER depreciation) is estimated to be around 20%. This estimate should be considered an upper bound given that future negative valuation effects may be smaller than it was the case in 2001-2007 period considered by Goldman Sachs.

While it is clear that estimates of the CA balance necessary to reduce the current NIIP position vary (due to different assumptions on real growth and interest rates as well as on the assumed target and timeline for the adjustment), there is no doubt that a significant reduction of the current NIIP would require at a minimum a balanced CA over the next two decades. Therefore, while the narrowing of the current account deficit observed in the last few quarters is a positive sign, it is far from what would be required to bring Spain's external position into sustainable territory. In particular, a transition from current account deficits to balance or even surplus requires a deep, structural re-adjustment of the Spanish economy.

Click to enlarge

External surpluses could be achieved by either expenditure reduction (reducing domestic demand) or expenditure switching through improvements in competitiveness. Expenditure switching would involve switching production towards the tradable sector and switching domestic demand towards a higher share of non-imported goods and services. Such expenditure switching should affect not only final goods but also intermediate inputs. Indeed, Spain is characterised by a relatively high import content of its exports compared to its main European peers (see Cabrero and Tiana (2012)). The lack of vertical integration of Spanish firms and/or the lower competitiveness of Spanish intermediate suppliers, possibly due to their small size, could explain this result. As a result, an increase in Spanish exports also has a relatively large positive impact on Spanish imports and, hence, the net (positive) impact on the trade balance is reduced. In addition, Spain faces several other obstacles to reducing its trade balance (see Section 3.4 on the competitiveness and export performance).

In addition, a shift to current account surpluses requires a structural adjustment in terms of saving and investment decisions of all the sectors of Spanish economy (see Section 3.1 for more details on saving-investment imbalance).

The large imbalance in Spain's external position increases the vulnerability of the Spanish economy in terms of both potential financing problems and the interest burden. While the flow adjustment in terms of current account balance has been significant, it is far from sufficient. In order to restore the sustainability of its external position, Spain needs to move into a persistent current account surplus. A preferred adjustment path would involve a switch of resources from non-tradable to tradable sectors. That can be achieved by increasing the competitiveness of Spanish economy and further improving its export performance.

3.4. COMPETITIVENESS AND EXPORT PERFORMANCE

The external performance of the Spanish economy within the monetary union has been mixed. Spanish price competitiveness deteriorated significantly due to growth of wages in excess of productivity growth, resulting in an appreciation of its unit labour costs. However, ex-post competitiveness, that is the evolution of Spanish exports' market share, was relatively favourable compared to other euro-area economies (although it declined by 11.6% in 2006-2010, according to the MIP scoreboard, compared to the threshold of -6%).

3.4.1. Price and cost competitiveness

According to different proxies, Spanish economy lost its price competitiveness between 2000 and 2008 |12|. More specifically, the accumulated REER appreciation was around 20%, with the exception of the REER based on unit labour costs vis-a-vis IC35, in which case the accumulated lost was 29% (Graphs 20 and 21) |13|. The relatively worse development of price competitiveness vis-a-vis IC35 rather than vis-a-vis the euro-area countries mainly reflects the appreciation of euro in that period (around 24% against the US dollar). All in all, independently of the indicator used, the loss of competitiveness for the Spanish economy was significant. The following sub-sections describe in greater detail the factors behind this loss of competitiveness.

Click to enlarge

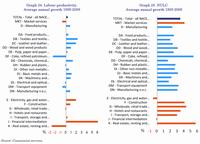

Very low productivity growth, 0.4% on average, and high growth of wages, 3.6% on average, over the period of 1999-2008, lie behind the deterioration of price competitiveness recorded during the same period. Low labour apparent productivity levels, generally below those of other EU countries were partly the result of the large share of construction sector in Spanish GDP. This sector tends to be characterized by below-average productivity since it is very labour intensive. However, other sectors of the Spanish economy also experience relatively low productivity, with manufacturing having the largest gap compared to the euro-area average. Indeed, according to Fedea-McKinsey (2010), productivity levels in Spain's manufacturing sector are 15% below those in EU-15 and 40% below the United States. During the boom period, growth in Spain was driven mainly by strong growth in labour utilisation, while productivity (measured by TFP) had a negative contribution. The main reasons for such a poor performance include the highly fragmented business fabric, significant net migration, which contributed to job creation in low skills and low productivity sectors, and institutional factors including relatively limited spending on R&D and innovation as well as an onerous regulatory environment for businesses.

Where firm structure is concerned, more than half of workers in Spain are employed in small companies (below 50 employees) compared to 23% in Germany and 32% in France. Even more strikingly, over 90% of firms are micro-firms (less than 9 employees and with a turnover below EUR 2 million) compared to 83% in Germany. These very small companies tend to be characterised by lower levels of productivity; thus, a larger share of smaller companies also implies a lower average level of productivity. At the same time, it is worth noting that large Spanish companies are equally, or even more, productive compared to their European peers. Indeed, Fedea-McKinsey, op. cit. demonstrate that Spain would have a 30% higher level of productivity than Germany if it maintained current productivity levels but changed its company-size mix to resemble that of Germany. In a similar vein, Altomonte et al. (2011) estimate that Spain's exports would be 25% higher if it had the same industrial fabric as Germany. There are several explanatory factors behind firm distribution in Spain, from the sector specialization pattern to possible regulation with lock-in effects that act as a barrier to firms' growth.

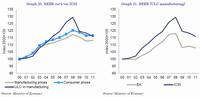

3.4.3. The development of unit labour cost

In the boom years, Spain's price and cost competitiveness deteriorated sharply driven by high growth of wages well above the corresponding increases in productivity, and leading to growth of ULC exceeding the euro-area average (Graph 22). High growth of wages was supported by a booming domestic economy and decreasing unemployment. Apart from cyclical factors, the evolution of wages was also influenced by the collective bargaining system and by the structure of the labour market, more generally.

Click to enlarge

The phenomenon of strong ULC increases across most sectors over the period 1995-2009 contributed to the loss of aggregated competitiveness in Spain. The only two exceptions were: "financial intermediation" and "electricity, gas and water supply" (Graph 24). In addition, market services experienced significantly higher ULC growth than manufacturing. It might be argued that cost developments in services - being mostly non tradable - are of little relevance when considering international competitiveness. However, services are an important input in manufacturing exports and could worsen the external competitiveness of goods to the extent that the deteriorations in the cost competitiveness of services are passed through to the final cost of tradables. Indeed, the services content of manufacturing exports in Spain is close to one third of the exports value and this share has increased over years |14|. In addition, empirical analysis shows that labour productivity of domestic services has a significant impact on export growth (about one-fourth of the effect of the REER) |15|.

Four services sectors - representing close to 60% of the market economy's value added - accounted for almost 80% of aggregate ULC growth in Spain between 1995 and 2009 (Table 2). In addition, services are characterized by a higher share of labour costs in the total output values as compared to manufacturing (Graph 25). That implies that the impact of wage developments on total costs in services is relatively more important.

Click to enlarge

3.4.4. Labour market and competitiveness

The collective bargaining system, which prevailed in Spain until the reform enacted on 10 February of this year, created additional rigidities in the responsiveness of wages to economic and firm-specific conditions since wage agreements took place mainly at industry and provincial levels. Empirical evidence (e.g. Izquierdo et al. (2003)) suggests that wage increases tend to be higher at the intermediate level (i.e. provincial industry level) than at the national and company levels |16|, while the wage distribution is more compressed compared to fully centralised or fully decentralised levels. In addition, the predominance of provincial and industry agreements left little room for negotiations at the level of the individual firm. Moreover, the so-called "ultra-actividad" clause |17| reduced the opportunities for renewing a contract without improving its conditions. Finally, wage indexation was also present in most collective agreements, although it was not prescribed by law. Both "ultra-actividad" and wage indexation contributed to a further acceleration of wages in the context of a booming economy.

Click to enlarge

The duality of the Spanish labour market was rooted in high employment protection for regular permanent contracts and low protection for temporary contracts coupled with a high turnover rate in temporary jobs and low conversion rates from temporary to permanent contracts. It induced firms to respond to economic fluctuations through high turnover at the margins of the labour market. The volatility created by the dual labour market generated strong job creation in booms and exacerbated job destruction during recessions. In addition, this system facilitated job creation in less-productive industries, which required less-qualified workers, which are over-represented among temporary workers. Finally, this duality had a pervasive impact on the wage developments, reducing the responsiveness of wages to the economic conditions. This was particularly acute in 2009, but also to a lesser extent in 2010 when Spain entered into a recession and the unemployment soared while the impact on wages was much more muted. As the job destruction was concentrated among the temporary workers, characterised by lower wages as well as lower bargaining power as compared to the permanent workers, its impact on wages was somewhat limited. All in all, the duality of the Spanish labour market contributed to a lower productivity as well as pervasive wage dynamics. Recently adopted labour market reform aims to reduce the duality and to increase the responsiveness of wages to firm-specific conditions (see the Box 4 on the summary of the labour market reform and Section 2.3 of the SWD 2012 for more detailed discussion).

Box 4: Labour market reform - summary and assessment On 10 February 2012, Spain adopted a comprehensive labour market reform which entails substantial changes to employment protection and collective bargaining. The reform was adopted through a Royal Decree law and entered into force immediately with its publication. In addition, a legislative proposal adopted by the government is currently under discussion in Parliament and takes additional steps in the same direction followed by recent reforms, while introducing some new elements notably regarding collective dismissals and employment protection in SMEs.

Salient features of the reform

Changes to employment protection aim to foster job creation and reduce labour market duality by lowering the gap in employment protection between permanent and temporary contracts. The reform reduces the severance payment for unjustified dismissals from 45 to 33 days per year of service, up to a maximum of 24 months. The reform also removes the worker's right to receive wages for the whole duration of a process against unfair dismissal (the so-called "salarios de tramitacion") in case the courts accept an appeal. The conditions for justified dismissals on economic grounds, which imply a reduced severance pay of 20 days per year of service, are clarified and made more specific, with a view to reduce legal uncertainty.

A new labour contract for SMEs and targeted subsidies aim to promote job creation in small businesses. The reform introduces new open-ended contract for SMEs with less than 50 employees, which includes a trial period of 1 year, incentives of up to EUR 3000 for hiring first-job workers below 30 years of age, a tax deduction equivalent to 50% of the unemployment benefits to which the hired worker is entitled, and additional hiring subsidies for young and long-term unemployed. Most of the incentives are conditional on keeping the worker for at least 3 years.

Changes to collective bargaining increase flexibility at firm level and give precedence to firm-level bargaining. Employers have the possibility to opt out from collective agreements for economic (fall in revenues or sales for at least 2 consecutive quarters), technical or organisational reasons via an agreement with workers' representatives. Moreover, firm-level collective agreements (concluded with union representatives) effectively prevail over other levels on a wide range of issues, including working conditions, wages, paid overtime, working time and other elements covered by higher level agreements. The indefinite extension of expired and not-renewed collective agreements (so-called "ultra-activity") is limited to a maximum of 2 years. In the absence of mediation and/or arbitration procedures, the collective agreement will no longer be in force and the higher-level collective agreement will apply instead.

Active labour market policy measures aim to improve employability and provide financial incentives for hiring employees. Temporary work agencies are allowed to operate as recruitment and placement agencies alongside the public employment service. Employees with seniority of at least one year are entitled to 20 hours of professional training per year in the form of a paid leave for training. The age limit to conclude apprenticeship and training contracts is raised to 30 years as long as the unemployment rate remains above 15%.

Assessment

The labour market reform represents a decisive progress, more ambitious than previous reforms in this area. The reform contributes to increasing labour market flexibility by providing for greater flexibility at company level and by setting conditions for a more rapid adjustment of wages. Notably, the reform includes a sizeable reduction in the costs of dismissals for permanent contracts both directly through lower severance payments in case of unfair dismissals and indirectly via a broadening of the definition of justified dismissals.

The effects of the reform are however made uncertain by a number of elements. First, the elimination of the "express" dismissal and of the prior administrative authorisations for collective dismissals might lead to an increase of legal disputes. Second, the reform re-establishes the limitations introduced by the 2010 reform on the renewal of temporary contracts. Specifically for SMEs, the new contracts with extended trial periods can become a substitute for temporary contracts. It remains to be seen, however, to what extent this will lead to a greater use of permanent contracts and greater employment stability. The possibility for a worker to be hired with consecutive apprenticeship contracts, which can be terminated at zero costs, goes in the opposite direction of that envisaged by the reform. The costs of dismissal for permanent contracts also remain high compared to those for temporary contracts. Finally, financial incentives for employment creation risk being a costly and inefficient labour market instrument.

Greater decentralisation of collective bargaining is an important element to improve the flexibility of the labour market. The priority given to firm level agreements, by allowing firms to derogate from sector agreements, and the introduction of binding arbitration (if other dispute resolutions are not established in inter-professional agreements) point to an effective decentralisation of wage bargaining. The limitation of "ultra-activity" may contribute to reduce the inertia of the collective contracts and to increasing the opportunities for renewing a collective agreement without improving necessarily its conditions. To the extent that large firms have stronger bargaining leverage than small firms, the reform benefits large firms in particular. The decentralisation of wage bargaining could favour a reduction in the very high level of structural unemployment. However, the effectiveness of the reform will ultimately depend on the use of firm-level bargaining in practice.

The reform has not tackled the practice of ex-post inflation wage indexation usually applied in collective agreements. However, a recent social partners' agreement effectively suspended wage indexation for the period 2012-2014. The ultra-activity limit of 2 years still appears to be too long and opting-out clauses might not be easy to implement for SMEs.

3.4.5. Export and import developments

Spain's world market share in goods and services exports has decreased somewhat, (Graphs 26 and 27). However, this decline has been less pronounced than in the case of other euro-area countries (with the sole exception of Germany). According to the WTO data, Spain's share in world manufacturing trade has been relatively stable at around 2% (higher for automotive products - around 5%). Regarding services trade, Spain's share in world exports has oscillated at around 4%. Spain's share in world exports of tourism services fell but this fall was compensated by an increase in export shares of commercial and transport services. Indeed, exports of tourism services seem to have exhausted their sources of growth. At the same time, non-tourism services have grown robustly (by 9% in 2011), reaching over 57% of total export of services in 2011. The main driver has been services to firms, probably related to Spanish direct investments abroad, which recorded significant rates of growth.

The relatively resilient performance of Spanish exports is somewhat counter-intuitive given the loss of price and cost competitiveness vis-a-vis other euro-area members since 1999. Empirical evidence suggests that improvements in total competitiveness (through higher value added or product differentiation), specialization in products with a low price elasticity (medium and medium-low technology content), and geographical diversification are the most important drivers of this comparatively better performance of Spanish exports.