| Report |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Report |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

01Sep17

Catalonia's Legitimate Right to Decide

Paths to self-determination

Back to topTable of Contents

Introduction. Exploring the Legitimacy Paths for the Right of Catalans to Decide on Their Political Future in Europe

The Working Method

The Substance of the IssueI. Historical, Political and Sociological Background for the Current Situation in Catalonia

1.1. Catalan Party System and Territorial Preferences within Catalan Political Parties

1.2. Catalan-Spanish Negotiating Process and the Tortuous Path to a Legally Binding Referendum1.2.1. Between 1980-2003: a "fish in a bag" strategy 1.2.2. Between 2003-2012: a "hard ball" strategy

1.2.2.1. From 2003 to 2006: Tripartite Coalition of PSC-ERC-ICV-EUiA

1.2.3. Since 2012: a "chicken" strategy

1.2.2.2. Between 2006 and 2010: PSC-ERC-ICV-EuiA

1.2.2.3. Between 2010 and 2012: CiU1.2.3.1. Between 2012 and 2015: Minority Government of CiU with the support of ERC

1.2.4. Intermediary Conclusion

1.2.3.2. Since September 2015: Junts pel Sí CoalitionII. Foundations for Catalonia's Right to Decide its Political Future

2.1.1. The Emergence of Secessionist Popular Demands: A bottom-up and top-down Movement

2.1.2. The Role of Organized Civil Society in Catalan's "Right to Decide" 2.1.3. Survey of Catalan Public Opinion: What does Catalonia Want?

2.1.4. Catalan Public Opinion and Voting Behavior: Who voted What?

2.1.5. Is Nationalism the Cause of Increased Demand for Independence in Catalonia?

2.1.6. Intermediary Conclusion2.2.1. Demystifying parochialism

2.2.2. The Horizon of Constitutional Contractualism

2.2.3. The Ethics of the Right to Decide2.2.3.1. The "Just-cause theories" justifying the exercise of the Right to Decide

2.2.4. The Democratic Justification for the Right to Decide

2.2.3.2. The "Choice theory" justifying the exercise of the Right to Decide

2.2.3.3. The "Collective Autonomy theory" justifying the exercise of the Right to Decide

2.2.5. The Conditions of Decision-making

2.2.6. Intermediary ConclusionIII. Can the "Right to Decide" be Legally Denied?

3.1. Catalonia's Right to Decide its Political Future under International Law

3.1.1. International Case Law: The International Court of Justice Kosovo Advisory Opinion and its Relevance

3.1.1.1. Facts of the Kosovo Advisory opinion

3.1.2. State Practice Recognizing the Right to Decide 3.1.3. Review of State Practice Regarding Sub-State Entities Exercising Their Right to Decide since 1991

3.1.1.2. Procedural Posture of the Case Before the International Court of Justice

3.1.1.3. Question Presented

3.1.1.4. Holding in Kosovo Advisory opinion

3.1.1.5. The Court's Analysis

3.1.1.6. Referenda Could Be a Preferred Means for Exercising the Right to Decide

3.1.1.7. Application to Catalonia

3.1.4. Intermediary Conclusion3.2. Catalans' Right to Decide on Their Political Future under European Law

3.2.1. EU Law Does Not Prevent the Exercise of a Democratic Right to Self-determination

3.2.1.1. The Absence of Specific Treaty Provision on the Right to Self-determination prevents action by EU institutions

3.2.2. EU Law Implicitly Recognizes in its Founding Treaties the Right of European Peoples to Self-determination

3.2.1.2. No Disposition of the EU Treaty Allows the Spanish Government to Prevent the Exercise of Democratic Self-determination3.2.2.1. The Right to Decide as a European People under EU Law

3.2.3. EU Recognizes the Right to Self-determination of Peoples as a Fundamental Rule of International Law3.2.2.1.1. The Right to Decide as the Nation of an European State

3.2.2.2. The Right to Decide as a Collectively Exercised Individual Human Right

3.2.2.1.2. The Right to Decide as a European people without a State

3.2.2.3. The Right to Decide as a Right of EU Citizens Members of a European People without a State

3.2.4. The Constant Practice of EU Institutions and Member States Shows Support for the Exercise of the Right to Self-determination3.2.4.1. The Constant Practice of Supporting Accession to the EU for New European States Having Emerged through the Exercise of Self-determination

3.2.5. Intermediary Conclusion

3.2.4.2. The Right to Decide Recognized through the Practice of Self-determination Referendums Held on the Territory of Member States3.3.1. The role of Constitutions as Fundamental Norms

3.3.1.1. The Entrenchment of Constitutional Norms

3.3.2. Constitutions as "Essentially Contested Norms"

3.3.1.2. The Enforcement of Constitutional Supremacy3.3.2.1. Debating Constitutional Rigidity

3.3.3. Intermediary Conclusion

3.3.2.2. Debating Judicial Supremacy in Constitutional EnforcementIV. Is the Organization of a Referendum on 1st October 2017 by the Catalan Authorities Legitimate?

4.1. Potentially Conflicting Legitimacies

4.2. The Three Possible Paths for Materializing Catalans Right to Decide

4.2.1. Negotiations with the Spanish State on the Condition of Exercise of the Right to Decide

4.3. Behaving as regard the Exercise of the Right to Self-determination

4.2.2. Unilateral Organization of a Self-determination Referendum

4.2.3. Negotiating with Spain under the "Earned Sovereignty Framework" within the EU

4.4. Intermediary ConclusionReferences

About the authors

Acronyms and Abbreviations

Notes

Introduction

Exploring the Legitimacy Paths for the Right of Catalans to Decide on Their Political Future in EuropeCatalonia's decision to convene a referendum of Self-determination on October 1st 2017 constitutes a major challenge for Catalonia, as well as for Spain and the European Union. Scholars from all over Europe and beyond have been studying the recent self-determination trends that have their most salient expressions in Scotland (a self-determination referendum was held on 18 September 2014), the Brexit vote (23 June 2016) and Catalonia's claim for self-determination. Numerous conferences, workshops, articles and books flourish on the topic. However, contrary to the Scottish and British referendums, the legality of the Catalan referendum is heavily contested by Spain national authorities, raising a legitimacy issue; not about the outcome, but about the process itself. This is these legitimacy issues of the process itself, the question of the legitimacy of the exercise of a right to decide by a people without a State within the EU, that the present report explores.

The four international experts that produced the present report have been invited by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Institutional Relations and Transparency of the Government of Catalonia, to examine the legitimacy of the call for a Self-determination Referendum by the Catalan Government before the end of 2017 (the date of 1st of October has been announced since). They worked intensively during the recent months to produce this report. It is based on their previous expertise as well as an evaluation of the available documents, statements and publicly known acts |1| of the different actors involved in the present situation linked to the claim by Catalan government to exercise the Catalans' Right to Decide about their political future.

The framework of this study is multilevel, as it examines the arguments of parties within the Catalan, the Spanish, the European and the International contexts. The reality of 21st century Europe does not allow for actors at either level, to act in isolation or without reference to the other levels. And as is often the case with self-determination processes, the relevance of the different levels is contested. Therefore the dispute deploys its arguments at several levels of discourse, simultaneously debating the respective relevance of the different legal corpus in which the applicable rules have to be found and implemented, and about the substance of the rights to be respected or promoted.

This is why, despite being composed of several law professors, the present study does not aim at giving a legalistic answer to the issues at stake. As the Courts which have been asked to examine similar cases (the Canadian Supreme Court about the secession of Quebec in 1998, and the International Court of Justice as regard Kosovo's unilateral Declaration of independence in 2010) have both expressed, this is not an issue that may be solved by a pure legal proceeding; it ultimately calls for a political solution. Nonetheless, the political solution will have to be framed within the limits of fundamental principles structuring liberal democracies such as respect for democracy, the rule of law and fundamental human rights, principally. The present Report shows in that respect that the sometimes conflicting rights and principles have to be weighted against each other. This is why, while conducting a thorough political and legal survey of existing situations and arguments, the experts focus on the legitimacy of the respective claims and behaviors, and not on the identification of a legally enforceable solution.

Catalans constitute a European people without a State. In current international and European Law, "peoples" have the right to self-determination, meaning they can "freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development" |2| and thus choose for themselves a national project, which may lead to becoming a Nation-State. This right is recognized to "all peoples" and, contrary to a widely held belief, clearly not limited to people under colonial domination |3|. The States parties to the two 1966 UN Covenants on Human Rights "shall promote the realization of the right of self-determination, and shall respect that right, in conformity with the provisions of the Charter of the United Nations." |4| Spain, as all other members of the EU, has accepted these Covenants, and is therefore legally bound to respect the right for Catalans to exert self-determination. Therefore, the legalistic argument based on the 1978 Spanish Constitution, put forward by the current Government of Spain to refuse the exercise of the right to self-determination, is not valid and in clear contradiction with Spanish obligations under international and EU Law, that are binding on the Spanish national authorities according to sections 10 § 2 and 96 of the Constitution.

Catalans authorities are not claiming a right to self-determination, but rather the right to decide of their political future (see 2.1.5. below for the emergence of this concept). A political future that will indisputably be within the EU, and within or outside Spain, depending on citizens' choices and upcoming negotiations. Self-determination has been, since 1960 |5|, considered within the framework of the UN as a right grounded on a just cause (a form of remedial secession) for people under colonial domination. As we explore later in the report (see below point 2.2.3 on the ethics of the right to decide) this is only one of the ethical foundation of the right to decide. Political philosophy offers other justification for a people to claim the exercise for the right to decide. This is why, in the present report, we shall privilege the use of the right to decide over the right to self-determination, despite the fact that both concepts recoup in many aspects.

Further, the existence of such a Right in formal terms does however not exhaust the debate on the conditions under which its exercise may be legitimate. One of the well-known difficulties with the exercise of the right to self-determination as recognized in international law since the adoption of the UN Charter (1946), is that "peoples" "nations", and even "States" are not properly defined under international law |6|. This is largely due to the different co-existing conceptions of "nationalism" that were forged between the late XVIII and the XXth Century. The international Law right to self-determination does not make specific reference to any given conception of nationalism; it is however important to precise that Catalans' claim for the right to decide is grounded in the civic and liberal conception of a Catalan nation, and not an essentialist, "natural" or ethnic conception of the Catalan nation |7|, as is clearly demonstrated by the draft bill on the self-determination referendum presented by the Catalan government on 4th of July 2017. Such a democratic self-determination is the only type of national project that is in conformity with European values as enshrined in article 2 of the Treaty on the European Union (hereafter TEU).

With the civic liberal approach to a national project that Catalans promote for the exercise of their right to self-determination, the existence of a Nation is not a pre-existing sociological, historical and/or cultural fact - which once established (by whom is another question...) would then allow for the right to self-determination to be exercised (as a right of this pre-existing collective entity that would be an ethnic Nation) - but the result of a will to exert a national project, democratically expressed by the people which will, through this process, eventually constitute themselves as a sovereign nation. The most legitimate path to realize such national project is thus the organization of a referendum, based on a clear question that will allow for the Catalan people to decide on its own political future, by exerting self-determination.

Catalans have long shown their will to actively participate as a European nation to the peaceful development of Europe. Their contributions to the European project have been numerous, as shown below. Further, their contribution to the building-up and the stabilization of the democratic Spanish State following the regime of Franco is also undeniable. However, their current situation within Spain and EU, as a nation without a State, does not allow them to fully participate, on an equal footing with other European nations, to the crafting of the future of Europe. The Catalan nation has an equal dignity with all other European nations, and the exercise of the right to decide is the legitimate exercise of this equal dignity.

Actually, art. 49 of the Treaty on the European Union (TEU) recognizes that "any European State which respects the values referred to in Article 2 [TEU] and is committed to promoting them may apply to become a member of the Union". And as declared in the Preamble of the Rome Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (nowadays called the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union) by the States members of the EU, they are "calling upon the other peoples of Europe who share their ideal to join in their efforts." |8| This call to other peoples of Europe clearly concerns Catalans (as it did concern Croats, Czech, Estonians, Hungarians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Poles, Slovaks or Slovenes, and still address Basques, Catalans, Flemings, Norwegian, Scots or Swiss among others), but it requires for these people, in order to be able to answer the call, to first acquire their own State, in order to be able to become a full participant (member) of the EU, according to article 49 TEU procedure.

Thus current EU law actually encourages European peoples without their own State to first become a nation-state, in order to then fully participate to the European integration process as a member State of the EU. Some argue that EU should reform itself with a special procedure for dealing with case such as Catalonia's desire to become a full-standing EU member, without having to first become a European State outside EU in order to join, or even have a special enhanced regional status within the EU |9|. Such proposal does make sense and could be explored within the emerging framework of "earned sovereignty" (see sections 3.2.4. and 4.2.3. below); it would however be for the current EU institutions or member States to initiate a Treaty revision (under the procedures of art. 48 TEU |10|) to deal with such situation. Under current positive law, Catalonia may not initiate a Treaty change, and therefore has to follow existing EU procedures to be able to fully and equally participate to the EU project. Even though the EU treaties do not have a specific clause dealing with the claim of Catalonia for self-determination before joining the EU as a full-fledged member States, as we will show below, no EU provisions forbids the exercise of the right to decide by a European people, and further, there is a consistent EU practice of recognizing and the result of self-determination process.

Therefore the present report does, through a thorough academic analysis, show that the claim by the Catalan democratically elected authorities of their right to decide is legally and politically legitimate. The holding of a self-determination referendum on the 1st of October 2017, prompted by the persistent refusal of the Spanish authorities to envisage any other way of dealing with the legitimate claim of the Catalan people for exercising their right to decide, appears at the time of the writing of this report, as the most straightforward and democratically legitimate way to exert this right to decide. This does not however, if other actors (Spanish national Authorities or European Institutions) were to propose dialogue or negotiation, precludes Catalan Authorities to continue searching for a negotiated solution within the Earned sovereignty conceptual framework, within the EU institutional frame.

I. Historical, Political and Sociological Background for the Current Situation in Catalonia

Since the re-establishment of democracy in 1977, Catalan governments have repeatedly made demands of self-government. In spite of a federal and gradualist position assumed by Catalan parties in office between 1980 and 2010, concessions have been rather modest. Indeed, the growing resistance of the Spanish government to negotiate has become salient over the years, and reached its peak in 2010 with the Constitutional Tribunal ruling on the revised Statute of Autonomy of 2006.

In this chapter, we will illustrate the Spanish government's behavior in regard to the Catalan self-determination process. This section will be organized as follows. We will first present the Catalan party system and identify Catalan territorial preferences within Catalan political parties. We will then move towards particular aspects and moments of Catalan-Spanish negotiating process on the tortuous path to a legal referendum on the right to decide. Mapping Catalan political parties' territorial preferences will ease our understanding of the negotiating process that has taken place between the Spanish and Catalan governments since 1980.

Ultimately, this combined approach will allow us to confirm Spanish government's resistance in making concessions through time which has contributed to fuel the popular support towards political independence. As we shall see in chapter II, this bottom-up movement has grown rapidly with the release of the Constitutional Tribunal ruling in 2010. Furthermore, it has been reinforced in 2012 by the Spanish state's prohibition to hold a referendum as the CiU started to prioritize calls for a referendum on independence in reaction to the Spanish government's refusal to agree on a new fiscal pact for Catalonia.

In conclusion, we will posit that it is an increasing dissatisfaction towards the outcomes of the negotiating process between the Spanish and Catalan governments that has led Catalan pro-independence political parties into a patriotic political compromise moving beyond ideological divergences to argue for Catalonia's "right to decide".

1.1. Catalan Party System and Territorial Preferences within Catalan Political Parties

The Catalan party system is structured in a bimodal axis of competition, including the classic ideological dimension (left-right) as well as center-periphery dimension, commonly known as the Catalan-Spanish nationalist debate.

Historically, in Catalonia there had been five main political parties achieving representation both in the regional and national parliaments. First, Convergència I Unió (CiU) was a federation of the center-right Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya (CDC) and the Christian-Democrat Unió Democràtica de Catalunya (UDC). The federation, headed by former leader Jordi Pujol, ruled the Catalan government uninterruptedly from the first Catalan elections in 1980 until 2003.

The political formation had largely favored a gradual system of increasing self-government, although since 2012 CDC geared in an undecided camp, balancing between the status qui and a confederation. The discrepancies between the two parties regarding the secession of Catalonia entailed, in June 2015, the dissolution of the federation and the decision of each party to compete separately in 2015.

The second party in importance has traditionally been the Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya (PSC), a center-left and pro-federalist party, federated with the Partido Socialista Obrero Espanol (PSOE). The party has historically won the elections for the Spanish Parliament in Catalonia, while it has traditionally been the second force in the Catalan elections.

The Partit Popular Català (PP) is the regional branch of the Spanish Partido Popular (PP). It is a rightist party that is in favor of the status quo or even of recentralizing some powers granted to the regions. The national party was founded in 1989 as the heir of the former Alianza Popular, a party created by several leaders of the Francoist dictatorship. The party has never been in power in Catalonia although it provided support to the CiU government during the 1999-2003 legislature.

Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC) is a leftist and pro-secession party. Founded in 1931 before the Spanish second Republic, the party held the presidency of Catalonia from early 1931 until the Francoist coup d'état. During the dictatorship, ERC maintained the Catalan government in exile and it was not legalized until after the first general elections. At the dawn of democracy, the party embraced pro-sovereignty postulates, although it was not until 1989 that it assumed the objective of full independence in its manifesto. ERC formed part of the Government from 18 June 1984 to 27 February 1987, when Joan Hortalà was the minister for Industry and entered into government for the second time in 2003 with the tripartite coalition with PSC and ICV-EUiA. Very seemingly, in 2015, ERC entered once more into government within the pro-dependence coalition Junts pel Sí (JxS) - Together for Yes.

Finally, Iniciativa per Catalunya Verds-Esquerra Unida I Alternativa (ICV-EUiA) is a leftist, green and pro-federalist coalition of parties. ICV is a federation of communist and socialist parties that came together in 1987. EUiA is a coalition of leftlist and communist parties split from the Spanish Isquierda Unida (IU) in 1997.

More recently, traditional parties were challenged by the entry of three new parties into the Catalan political arena - Ciudadanos (C's), Candidatures d'Unitat Popular (CUP) and Podemos (P). Ciudadanos ran for a Catalan election for the first time in 2006 when they won three MPs and kept them all in 2010. The party defines itself as anti-nationalist and constantly denounces the excesses and lies of Catalan nationalism, while arguing that Catalonia is, according to the Spanish Constitution, a nationality and already enjoys substantial self-government. According to C's, the independence debate is radically against the Constitution and they completely reject the 'right to decide' on the grounds that sovereignty lies with the Spanish people as a whole.

Candidatures d'Unitat Popular (CUP) is a left, pro-Catalan independence political party with a critical European stance that ran for the Catalan election in 2012. CUP has traditionally focused on municipal politics, and is made up of series of autonomous candidatures that run in local elections. Finally, Podemos - which in the case of Catalonia has a regional replication, the coalition Catalunya Sí que Pot (CSQP) - is a left party that was established in 2004. Although it precludes a popular consultation on the future of Catalonia, they do not assume a clear position in regard to their territorial preference for Catalonia.

1.2. Catalan-Spanish Negotiating Process and the Tortuous Path to a Legally Binding Referendum

In this section, we will review the most relevant moments and strategic "options" made by Catalan governments over the years since the re-establishment of democracy in 1977. The purpose of this exercise is to identify key political actors who have contributed to Catalan self-determination process. Additionally, this will allow us to acknowledge how many times the Spanish government has rejected Catalonia's request to hold a legal binding referendum on political independence. In order to accomplish this task, we will go through the evolution of the agreements and disagreements achieved between the Catalan and Spanish governments through time.

For the purpose of clarity, we will argue that since the reestablishment of democracy negotiations have gone through three different types of negotiating strategies: the first one is popularly known as "fish in a bag" |11| strategy (1980-2003); the second one is called "hard ball" strategy (2003-2012) and the third one is called "chicken strategy" (2012-today). On the basis of this analysis, we will conclude that the political pay-offs have been increasingly unsatisfactory on the Catalan side, leaving a strong sense of dissatisfaction among Catalan people which has contributed to fuel increasing demands of political independence since 2010.

1.2.1. Between 1980-2003: A "fish in a bag" strategy

"Fish in a bag" strategy can be defined as a cooperative strategy where both parties agree to negotiate and to make concessions in order to reach mutual gains. This strategy denotes a situation when both sides of the dispute feel that they will benefit from the resolution of the conflict (win-win situation). In this type of negotiation, "mutual confidence" is key as well as the "willingness" to preserve the relationship. This type of strategy can be used to label the years that go from 1980 to 2003 when Catalan governments were presided by Jordi Pujol on the Catalan side, leader of the center-right moderate nationalist coalition CiU.

At the same time, the two-main national Spanish parties, either with right or left-wing orientation - Partido Popular (PP) and Partido Socialista Obrero Espanol (PSOE), respectively - were in charge of the Spanish governments. The presidents of the government were Filipe Gonzalez (PSOE) from 1982 to 1996 and Jose Maria Aznar (PP) from 1996 to 2004. Between 1980 and 2003, irrespective of Jose Maria Aznar's government (2000-2004) lack of response to demands for greater autonomy for Catalonia, the relationship was still based on trust and commitment.

1.2.1.1. From 1980 to 2003: Majority Government of CiU

Since 1979 the political scenario in Catalonia has always had some important differences with respect to Spain. From the first Catalan Parliament, held in 1980 to 2003, the regional Catalan government was in the hands of a long-term collation of two centrist moderate nationalist parties: Convergència I Unió (CIU) formed by Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya (CDC) and Unió Democràrtica de Catalunya (UDC). Jordi Pujol, the leading figure of the coalition, was the president of the Generalitat for the whole period.

Jordi Pujol, once President of the Generalitat, focused his political strategy on the achievement of a rapid transfer of powers from the central government to the autonomous institutions, a process that to a great extent was facilitated by Adolfo Suarez, then Prime Minister of Spain and one of the main figures in the transition to democracy. This took place at a time when Suarez's party, UCD (Unión del Centro Democrático) needed CiU's support to secure a majority in the Spanish Parliament. However, the 1981 attempted coup d'état prompted a U-turn in central government policies. The newly appointed Prime Minister, Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo, under pressure from the conservatives, halted to any further devolution of powers to the autonomous communities |12|.

Therefore, although this phase was characterized by permanent political and legal disputes about the jurisdiction of the Catalan and Spanish governments on all sorts of policies the distribution of fiscal revenues or the degree of devolution considered adequate, Pujol favored a strategy of permanent bargaining with the central government in order to gradually extract small concessions to increase the capacity of self-government of the Catalan institutions |13|.

Between 1980 and 2003, Catalan governments have been committed to the project of a federal Spain, while pursuing an agreement that could benefit Catalonia. Very seemingly, Spanish governments have been relatively engaged in negotiation but soon after the 2000 landslide victory of José M. Aznar's conservative Popular Party (PP), sympathy and understanding towards Catalan's demands for further autonomy and recognition were replaced by hostility.

1.2.2. Between 2003-2012: A "hard ball" strategy

A "hard ball" strategy can be defined as a competitive strategy where parties find it difficult to reach a compromise because one of the parties is not interested in making any concessions. This strategy denotes a situation when only one side perceives the outcome as positive (win-lose situation). As a reaction to this offensive strategy, the other party reacts using all possible means to persuade and force the competitor to make concessions. This type of negotiation is highly competitive and it is based on suspicion and distrust. This negotiating strategy could be applied to the relationship established between the Catalan and Spanish governments between 2003 and 2012 as the revision process of the Catalan Statute of Autonomy was hampered by the Spanish government leading to a growing dissatisfaction with the degree of autonomy conceded.

1.2.2.1. From 2003 to 2006: Tripartite Coalition of PSC-ERC-ICV-EUiA

The pattern of nationalist hegemony was broken in 2003 by the election of a tripartite coalition led by the PSC under Pasqual Maragall, which also included ERC and Inictiativa per Catalunya Verds - Esquerra Unida I Alternativa (ICV-EUiA - Initiative for Catalonia Greens-United and Alternative Left). The new President of the Generalitat was Pasqual Maragall, the former socialist mayor of Barcelona. Once in power, Maragall was to propose the drafting of a new Statute of Autonomy for Catalonia; an updated much more ambitious statute than that of 1979.

This political élan towards more self-government was supported by José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the leader of the Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) and future Prime Minister of Spain, who during the election campaign of 2004 committed himself to supporting the new Statute. However, this turned out to be a much more complicated business than initially expected. Profound discrepancies emerged between Maragall and Rodriguez Zapatero (PSOE), who, once in government in 2004, proved unable, or unwilling, to stand up by his promise to support the new Statute of Autonomy to emerge from the Catalan Parliament.

Irrespectively of these major difficulties, a broad agreement was reached in the Catalan Parliament and on 30 September 2005, the Parliament of Catalonia passed its proposal for a new Statute of Autonomy. It was approved with the support of 120 MP's out of 135 and was sent to Madrid. The proposal to reform the 1979 Statue of Autonomy recognized Catalonia as a nation, preventing Madrid's interference in devolved powers, and giving Catalonia full control over a transparent and rational financial arrangement.

The CiU's pact with PSOE in 2005-2006 ensured the approval in Catalonia of a less ambitious text than the draft originally agreed upon by the tripartite coalition headed by Pasqual Maragall. The final text of the new Statute of Autonomy had been seriously watered down during the negotiation process to make it acceptable to the Spanish government and Socialist Party (the conservative party PP was opposed to it from start to end of the whole process). CiU's support for the eventual text of the reformed statute was crucial since this required a two-third majority in the Catalan parliament and then had a difficult passage through the Spanish parliament, where it was modified further.

The Statute that was finally approved in the Spanish Chamber of Deputies undermined many of the most ambitious competences recognized initially in the law passed by the Catalan Parliament. Despite this, a majority of the Catalan parties in the Catalan Parliament represented by CiU, PSC and ICV-EUiA accepted the agreement and the statue of Autonomy was brought back to Catalonia to be ratified in a referendum.

Finally, on the 18th of June 2006 the Statute of Autonomy was approved in a popular referendum in Catalonia with 74% of affirmative votes, but the turnout was relatively low (less than 49% of the electorate). Even though the level of self-rule that the new law granted for Catalonia was lower than the level bestowed in the original law voted by the Catalan Parliament, many people still considered that this was a significant improvement to fight for |14|. However, the climate remained calm only for a few weeks.

At the end of July 2006, the PP brought the approved Statute of Autonomy to the Constitutional Tribunal - arguing that some of its content did not comply with the Spanish Constitution. This generated a sense of outrage among Catalans who could not understand how the newly approved Statute - after following all the procedures and modifications as requested by Spanish political institutions and the Constitution - could still be challenged. The reaction from civil society came immediately in 2006 and became stronger in 2007 with massive demonstrations. Catalonia would have to wait until the 28 June 2010 for the Constitutional Tribunal to release its final decision.

1.2.2.2. Between 2006 and 2010: PSC-ERC- ICV-EUiA

A new election took place in November 2006. Although CiU was, again, the winner, the three-left-wing-party coalition was re-edited, now under the leadership of the new president of the Generalitat, Jose Montilla, a former minister of the Spanish Socialist government. Despite the approval of the new Statute of Autonomy, the political situation did not become less agitated |15| for two main reasons: first, the PP had made the decision to take important parts of it to the Constitutional Tribunal (as we have mentioned before) and second, things started moving at the level of Catalan civil society.

New organizations other than traditional political parties were being created to successfully mobilize citizens in defense of the right to decide of the Catalan people. These groups organized for example a series of local unofficial self-determination referendums in almost 60% of all municipalities of Catalonia between 2009 and 2011.

In June 2010, after four years of deliberations, the Constitutional Tribunal of Spain, by a 6 to 4 majority of its members, decided to give an interpretation of 41 articles of the Statute that downplayed the autonomy-strengthening dimension - mainly those relating to language, justice and fiscal policy - thus watering down even further the main tool for Catalonia's self-rule. It also deleted the reference to Catalonia as a "nation". On 10 July 2010, a massive demonstration was once more organized on the streets of Barcelona as a form of protest.

1.2.2.3. Between 2010 and 2012: CiU

In November 2010, there was a new election to the Catalan Parliament. The clear winner was again CiU and a new governance was formed under the leadership of Artur Mas, Jordi Pujol's heir since 2003. The controversial 2010 Constitutional Tribunal ruling not only led CiU to redefine its territorial aims, but also radicalized other actors' objectives, most notably sectors of Catalan civil society.

In terms of policy, Mas outlined two main objectives for his term in office. First, he aimed at economic recovery in a context of a deep economic crisis; and, second, he promoted a new fiscal agreement ('pacte fiscal') for Catalonia with the Spanish government, involving the capacity of Catalan institutions to levy all taxes in Catalonia and also to reduce the indirect money transfers from Catalan tax-payers to other Spanish regions. This substantial fiscal demand was justified by CiU on account of a Constitutional Tribunal ruling on the 2006 reform of the Statute of Autonomy, which invalidated several articles and reinterpreted several others in a restrictive way.

The modification of a law that had been approved by Catalans in a referendum was viewed by CiU as totally unacceptable, and this led to a change in the discourse of main Catalan nationalism to the so-called 'right to decide' ('dret a decidir') of the Catalans. The first implication of this new framework was, therefore, the capacity to decide on the taxes that Catalans pay, and CiU made its proposal for a new fiscal deal. In this context, the Catalan parliament endorsed the demand for a new fiscal agreement that would imply full fiscal autonomy for Catalan institutions and a reduction of the solidarity transfers from Catalonia to the other regions. After the parliament's vote, Mas intended to negotiate this demand with Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and a meeting was scheduled for 20 September 2012.

However, Catalan civil society did not wait until the meeting took place and throughout the summer the Assemblea Nacional Catalana (ANC) called for a demonstration in Barcelona on Catalonia's national day, 11 September. Under the slogan 'Catalunya, nou estat d'Europa' ('Catalonia, new state of Europe'). In September 2012, as Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy (PP) refused to offer any specific proposals in political or budgetary terms for Catalonia and on the 27 of September 2012, the last effective day of the then incumbent legislature, the Catalan Parliament declared itself ready "to assume and develop the desires that the citizens of Catalonia expressed in a massive and peaceful way" |16|.

Owing to the effervescence of civil society and the rapid growth of associations such as the ANC and Ómnium Cutural (OC), the then President of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Artur Mas, called for anticipated regional legislative elections with the argument that there was strong pro-secession pressure exercised by civil society, particularly after the official dialogue with the Spanish government on a new financing system for the region and the rest of Spain's 17 autonomous regions.

1.2.3. Since 2012: A "chicken" strategy

A "chicken" strategy can be defined as a very competitive strategy which is characterized by a conflictual relationship. This strategy is defined by the absence of dialogue between parties after several attempts of unfruitful negotiations. This strategic option denotes a situation that is disadvantageous to all parties involved (lose-lose situation). On these particular cases, negotiators rely on the bluff tactic with a threatened action in order to force the other party to "chicken out" and yield to their demands. This strategy can be used to characterize the phase that started in 2012 as the escalation of the conflict between Catalan and Spanish governments led the Catalan government to prepare a referendum on political independence to be held on the 1 October 2017. This last strategic move was implemented with the attempt to bring the Spanish government back to negotiation.

1.2.3.1. Between 2012 and 2015: Minority Government of CiU with the support of ERC

On 25 November 2012, elections were held in Catalonia and secession became a salient electoral commodity for the first time since the transition to democracy in the second half of the 1970's. The result is that 80% of MPs in the new Parliament of Catalonia support the right to self-determination. The new Catalan Parliament had 107 out of 135 MPs supporting a self-determination referendum as the best way to find out what the majority of Catalans think about independence and as an effective way to channel the massive bottom-up pro-independence movement through the institutions.

At these regional parliamentary elections, CiU lost ground with respect of the previous regional elections (losing 12 seats in the Catalan Chamber) while ERC increased its constituency and added 11MP's to its previous parliamentary representation. ERC offered parliamentary support to a minority CiU government. The Agreement celebrated between CiU and ERC in December 2012 included the commitment to consult the Catalan people. Furthermore, on 23 January 2013, the Catalan parliament approved |17| and issued a Declaration on the sovereignty and the right to decide of the people of Catalonia with the support of 64% of the members of the chamber.

The declaration asserts:

"(...) The people of Catalonia have, for reasons of democratic legitimacy, political and legal sovereign personality (...) The process of exercising the right to decide shall be strictly democratic and it shall especially ensure pluralism and respect for all options, through debate and dialogue within Catalan society, so that the statement resulting therefrom shall be the expression of the majority will of the people, which shall be the fundamental guarantor of the right to decide (...)" |18|.

The declaration was significant, first, because it was facilitated by agreement of the two main Catalan nationalist parties, Convergència i Unió (CiU - Convergence and Union) and Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC - Republican Left of Catalonia), which historically have been electoral and political rivals in Catalan politics |19|. Second, the declaration paved the way for the holding of an unofficial consultative referendum on Catalonia's constitutional status in relation to Spain on 9 November 2014. At the end of 2013, after long negotiation, the political parties CiU, ERC, ICV-EUiA and CUP, which altogether represented 64,4% of the seats in the Catalan Parliament, came to an agreement to hold the referendum on 9 November 2014.

Additionally, on 16 January 2014, the Parliament of Catalonia made a formal petition asking the Spanish Government to transfer the necessary powers to hold the referendum (as Westminster did with Scotland) but this was denied by the two largest parties (PP and PSOE) with 86% of the votes of the Spanish Parliament. As a reaction to this overwhelming rejection, instead of calling a referendum under Catalan Statute 4/2010, the Catalan government and the majority of the Catalan Parliament were inclined to use a non-referendary popular consultation |20|.

The decision for the referendum to be conducted was not free of political tensions. The Spanish government challenged it in the Constitutional Tribunal, which declared - the same week of 9 November, a Sunday - that the vote could not go ahead. However, the Catalan government claimed that it was organized by volunteers and the 'participation process' took place regardless. This action led the Spanish attorney general to indict President Mas and two other regional ministers on several charges and the judicial process is still unresolved.

The consultation took place on the 9 November 2014, despite its legal prohibition and political rejection by the Spanish state. Over 2,3 million Catalans voted in the participatory process. The result - 80,8% in support of Catalonia's secession from Spain, on a turnout approximating 35% - was one of the biggest demonstration of growing support for a radical change in the scope and operation of Catalan self-government. Yet, Mas had previously declared that this consultation would not have any legal effect, and therefore the 9 November vote was seen more as a symbolic victory for the pro-independence movement and a demonstration of its strength, than as an actual mandate for independence.

In response to a growing popular discontent, on 25 November 2014, President Artur Mas defended the right of the Catalan people to hold a legally-binding vote on independence. On 3 August 2015, Mas called early elections - to be held in September 2015 - which would be used as a de facto plebiscite on independence. The announcement followed an agreement between CiU and ERC, with the support of representatives from the main civil society organizations supporting self-determination (ANC and OC).

1.2.3.2. Since September 2015: Junts pel Sí Coalition

At the elections of September 2015, the two main secessionist parties, CDC - Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya - and ERC, as well as DC (Demòcrates de Catalunya) |21|, the Democrats from the Moviment d'Esquerres (MES) and the Socialists AVANCEM-espai socialista, and most importantly, a broad swathe of independents of all political colors and origins, representing all classes of grass-roots and civic movements - ANC and OC - have run together under the pro-independence list Together for Yes (Junts pel Sí - JxS).

This single-issue coalition was established with the purpose to reinforce the 'plebiscitary' nature of the regional election. In terms of constitutional proposals |22|, JxS put forward a short roadmap to unilateral independence (to be achieved in less than 18 months), which would start following a victory of the pro-independence forces - JxS and the CUP - counted in seats, and not necessarily in votes. Raül Romeva, the current Minister for Foreign Affairs, Institutional Relations and Transparency headed the coalition.

In the non-secessionist camp, some calls were made by the PP to join forces with the PSC and C's but the PSC, traditionally a strong party in Catalonia now in decline, ruled out that option. Finally, ICV formed the coalition Catalunya Sí Que Es Pot (CSQEP) - Catalonia Yes We Can - with the emergent Spanish statewide party Podemos, which had been relatively successful both in the 2014 European elections and the May 2015 regional elections in Spain, along with other leftist parties.

The pro-independence coalition of JxS clearly won the election with 39.59% of the vote. Thus, the pro-independence parties obtained a majority with 72 seats: JxS had 62 seats, 6 short of a majority, while the CUP had 10 seats. Then pro-independence options obtained 47.80% of the votes. The parties against a referendum and against independence combined for a total of 52 seats: this included the second party in the new Parliament, C' s, with 25 seats, and the traditional statewide parties, the PSC and the PP, which fell behind with 16 and 11 seats respectively. Finally, the 11 MPs of CSQEP supported a referendum but did not position themselves on the independence issue (see table 1 below).

The pro-independence majority in seats was seen by JxS as a democratic mandate to start a process of secession of Catalonia from Spain. The CUP, for its part, initially admitted that the result of the pro-independence parties fell short of a majority in votes and therefore the plebiscite had not been won. Yet, the two parties jointly passed a resolution on 9 November 2015, a year after the symbolic consultation on independence, declaring the start of a process of disconnection from the Spanish state.

Table 1: Election results in Catalonia by constitutional option

Constitutional option Party Seats 2015 Seats 2012 Seats +/- Seats by bloc Vote % by bloc Pro-independence JxS 62 71 -9 72 47.8 CiU - 50 - ERC - 21 - CUP 10 3 7 Pro-referendum CSQEP 11 - -2 11 10.06 ICV - 13 - UDC 0 - 0 Against referendum, against independence C's 25 9 16 52 39.11 PSC 16 20 -4 PP 11 19 -8 N/A Others 0 0 0 0 1.12 Source: Departament de Governació i Relacions Institucionals (2015)

The resolution was passed with 72 votes, a majority of 5, but it was subsequently brought to the Constitutional Tribunal by the Spanish government and automatically suspended. Nevertheless, irrespective of the Spanish government's interference, since the Spanish Government has repeatedly proved his unwillingness to negotiate, the JxS is fully committed to the goal of political independence and to a legally binding referendum to be held on the 1st October 2017.

1.2.4. Intermediary Conclusion

In this chapter, we have looked at the evolution of the negotiating process between the Catalan and Spanish governments since the re-establishment of democracy in 1977 in Spain. By the means of a typology of three distinctive types of negotiating strategies - fish in a bag strategy (1980-2003); hard ball strategy (2003-2012) and chicken strategy (since 2012) - we have identified three phases of negotiation between the Catalan and Spanish governments throughout the years. The analysis of this negotiating process through time has allowed us to identify key moments of a deteriorating political relationship where the Spanish government - either led by PSOE or PP leaders - has gradually renounced to accommodate Catalan territorial demands. Very seemingly, the evolution of this relationship sheds a new light on the tortuous path towards the legally binding referendum on political independence to be held on the 1st October 2017.

II. Foundations for Catalonia's Right to Decide its Political Future

In this chapter, we will discuss the foundations for Catalonia's right to decide since 2006. In order to so, we will proceed in four moments: first, we will be looking at the emergence of secessionist popular demands since 2006; secondly, we will examine the role of organized civil society in Catalan's right to decide and thirdly, we will discuss the evolution of Catalan public opinion since 2006. Finally, in the last section, we will conclude that the growing popular support for political independence had nothing to do with "nationalism" in the sense that it was not primarily driven by identity issues but rather by the political demand for Catalonia - hereby perceived as a collective identity - to have the right to decide on its own political future.

If anything characterizes and distinguishes social and political life in recent years in Catalonia, it is the emergence of the debate on sovereignty. That is, the idea that the citizens of Catalonia must be the ones to decide their own future. However, the intensification of the political process towards further demands of self-determination and "the right to decide" cannot be dissociated from the role of organized civil society, on the one hand, as well as from a growing dissatisfaction with the degree of autonomy on the part of Catalan public opinion, on the other.

In this section, we will examine the role played by popular demonstrations, civil associations and political elites in a widespread support for the independence cause and the "right to decide" since 2010. Additionally, we will present the evolution of Catalan public opinion regarding territorial preferences and we will posit that nationalism does not hold the (full) explanation for an increased demand of political independence. By doing so, we wish to demonstrate that the shift towards pro-independence is the result of a changing perception about the possibilities of a significant accommodation within the Spanish framework rather than a change in Catalan nationalism.

2.1.1. The Emergence of Secessionist Popular Demands: A bottom-up and top-down Movement

As the Constitutional Tribunal released its decision in June 2010, the Catalan secessionist movement became much more active |23|, gathering popular and elite support to the independence cause. In face of the political deadlock imposed by the Spanish government, an important part of the population - political elite and civil society - started to defend Catalonia's right to decide its own future, as well as the option to become an independent state. With a series of political events, protests and other massive rallies, a large amount of the Catalan population put pressure on politicians and followed the political process |24|. Since the attempt to reform the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia and the tense process experienced by the Catalan population once the bill entered the Spanish Parliament, a vibrant and politicized civil society tried to progressively push the Catalan government and political parties into taking a stance on the issue of independence.

Some examples were the series of massive demonstrations organized since 2006 and the unprecedented popular referendums on secession organized between 2009 and 2011 in 552 towns in Catalonia. The massive demonstrations in 2006 and 2007 showed the incipient stages of what, a few years later, would turn out to be a vigorous and ideologically transversal active civil society supporting the right of the Catalans to decide their future. In this context, the decision of a Catalan municipality of 8.000 inhabitants near Barcelona to hold an unofficial non-binding referendum about the independence of Catalonia among its residents, and the fierce reaction of the Spanish government and the judiciary against it, portrayed a turning point in the recent history of the secessionist movement in Catalonia.

Additionally, in 2009 the local consistory of Arenys de Munt passed a motion in favor of holding a non-official referendum about the independence of Catalonia on 13 September 2009. In this regard, the Spanish vice prime Minister threatened the organizers with initiating legal proceedings, the public prosecutor lodged and appeal against the consistory's decision and a court eventually declared the collaboration of the local with the plebiscite illegal. With this popular initiative for "the right to decide", the phenomenon of unofficial referendums quickly started to snowball: on 13 December 2009, similar plebiscites were organized in 167 municipalities throughout Catalonia and in the months that followed several waves of referendum were held. Nineteen months later, 58,3% of the municipalities, representing 77,5% of the population, had held unofficial referendums. A total of 884.123 people voted with an overall turnout of 18,1%.

In 2010, the massive movements claiming independence reached the front lines and went on relentlessly organizing massive marches on 11 September for four successive years between 2012 and 2015. After the 2010's Constitutional Tribunal decision on the Catalan's Statute of Autonomy, Barcelona hosted one of the biggest demonstrations in Catalonia since the transition to democracy in the late seventies. A human tide marched on 10 July 2010 under the slogan "We are a nation. We have the right to decide". Although the demonstration was initially framed as a popular protest against the Constitutional Tribunal decision to curb some fundamental parts of the new Statue of Autonomy, it rapidly became a massive pro-independence claim.

In a similar line, on 11 September 2012, on the occasion of Catalonia National Day, another massive demonstration took place in the streets of Barcelona. The biggest demonstration in the history of Catalonia until then represented the highest peak of the first period of popular mobilization. The crowd marched on the streets of Barcelona under an explicitly secessionist slogan: "Catalonia, new state in Europe". On 11 September 2014, also on the Catalan National Day, 1.8 million people demonstrated in Barcelona to support the non-binding referendum of 9th November, forming a big mosaic of Catalan flag and a giant letter V standing for "Vote" and "Victory".

More recently, on the 11th September 2015, nearly 1.5 million Catalans took to the streets of Barcelona on Friday to rally for independence, as the region's politicians launched their campaigns for a looming election billed as a make-or-break moment for Catalonia. More recently, on the 11th of September 2016, hundreds of thousands do people rallied across Catalonia declaring their support for the autonomous region's full independence from Madrid. Demonstrators marched down Meridiana Street in Barcelona waving independence flags. Turnout was estimated by local police at around 800.000 but the central government insisted that only about 370.000 people attended these demonstrations.

These massive demonstrations organized by civil society organizations five times in a row is in fact an unusual political event and one could argue that a group can self-organize as a politically effective movement only when individuals perceive that their potential benefits are higher than their individual costs. Therefore, grassroots organizations promoting independence have successfully mobilized large fractions of the population because their cause, Catalan independence, has emerged as a natural aspiration that would bring large economic and political benefits. And this has occurred at a time when the cost of popular mobilization has greatly decreased |25|.

Grassroots associations engaged in a constant and prolific organization of political rallies that were innovative and rapidly attracted media attention, both inside and outside Spain. Although their specific goals sometimes varied, the ultimate objective of these efforts was dual: to force Catalan political partied to accept and negotiate a referendum on independence and, by convincing undecided individuals, to increase the pool of supporters for independence |26|.

On the elite side, intellectuals and cultural practitioners have always been a driving force in Catalanism throughout its history, the existence of autonomous political institutions since 1980 |27| has largely contributed to overshadow their role. However, with the recent shift in emphasis towards demands for independence rather than autonomy, the role of the cultural elites has once again become central to the Catalan's renewed movement of self-determination. This group of intellectuals and cultural practitioners includes the educated middle classes who have inspired the birth of Catalanism in the nineteenth century and led Catalonia's cultural resistance to the Franco Regime. However, in its contemporary manifestation, it also includes a broad spectrum of media professionals, whose influence is much more far-reaching, especially when these cultural and media elites have a sophisticated understanding of the power of social media |28|.

This new Catalan mobilization upsurge also identifies a second shift in Catalan protest as political and civil nationalist groups used to be traditionally known for gathering forces to oppose the idea of a Catalan independent state since both groups have always concentrated their demands that would make it easier for Catalans to keep their distinctive character while still being part of Spain. According to the historian Jaume Vincens Vives, this longstanding hesitation throughout the years can be explained in the light of the Catalan's inability to grasp state power. However, in the contemporary independence movement, the combination of top-down and bottom-up mobilization for the independence cause clearly emerged as a protest against the way power has been exercised by the Spanish State.

In fact, these massive movements, together with the outcomes of the opinion polls showing an increased preference for independence and the overall political climate, were clear demands directed at political leaders waiting for a government's response. Once more, the increase of popular demands has certainly forced President Mas to react, which he did right after the demonstration of September 2012 on Catalonia's day, the Diada. His response was to call early elections in order to obtain a mandate to organize a popular consultation on the issue. At that particular moment in time, Convergència i Unió (CiU), and more particularly the first government headed by Artur Mas, lived a key moment when their political discourse shifted decisively to one drawn from an overt pro-sovereignty |29| lexicon under the direct influence of a massive popular mobilization.

Undoubtedly, exclusion from power after 23 uninterrupted years in office gave a spur to CiU to reconsider its earlier ideological positioning. However, only from that moment on, did CiU, and especially the Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya (CDC) - the more "radical" partner in coalition - |30|, really prioritize calls for a referendum on independence, after central government had failed to meet the Mas administration's more limited demands for a new and special financing model, based on a fiscal pact, in recognition of Catalonia's history, economic situation and national status. Ultimately, and very directly, CiU was influenced by pressures from civil society.

As a result of the early elections, the Catalan Parliament was constituted by a large majority (79,2%) of members whose parties' campaign manifestos included support for holding a popular consultation over independence during the legislature. And most of the parties that formed this majority have since struggled to try to hold such a popular consultation. Indeed, the strength of the pro-independence claims expressed by relentlessly massive demonstrations and consistent support for a separate state in the polls, and the entry of three new parties into the Catalan political arena - Ciudadanos (C's), Candidatures d'Unitat Popular (CUP) and Podemos (P) -, faced the established five parties - Convergència i Unió (CiU), Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya (PSC), Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC), Partit Popular Català (PP), Iniciativa per Catalunya Verds-Esquerra Unida I Alternativa (ICV-EUiA) - with a new electoral scenario led to a period of major changes in Catalan and Spanish politics.

Although a majority of parties seeking the referendum - CiU, ERC, ICV-EUiA and CUP - won the majority at the election of November 2012, with 87 seats out of 135 seats, far above the overall majority, popular mobilization did not end. In 2013, civil society constituted the National Pact for the Right to Decide, a civil platform that sought support for the organization of the referendum. More than 8000 associations signed the Pact, including the main trade unions and most business associations and professional organizations. In addition, during September and October 2014, up to 920 towns councils approved the declaration in favor of the referendum. Efforts increased when the popular consultation on independence was scheduled for 9 November 2014.

The grassroots organizations promoted massive mobilization by which a major switch in the political preferences of the Catalan electorate was structured. Their role in determining the political agenda turned them into the most relevant new actor in the political landscape. Ultimately this bottom-up structure caused political parties to react and as a reaction to this pressure, since the end of 2012, the Catalan government has effectively tried to find effective ways to allow Catalan citizens to vote in a referendum about the future political status of Catalonia. As a last resort, Artur Mas and his allies in the pro-independence camp decided to call a new early election on 27 September 2015 and frame it as a plebiscite on independence.

At these elections, the pro-independence parties jointly secured 72 seats. President Mas quickly remarked that this result represented a great strength and strong legitimacy to keep on with the idea to hold a referendum on political independence. Nevertheless, he was to face |31| a tortuous road ahead: a difficult negotiation to form a Catalan government and, above all, the frontal opposition of the Spanish government and main political parties to any move towards secession or even the holding of a proper referendum on independence. However, irrespective of these major difficulties, it is undeniable that these bottom-up and top-down movement played a significant role in the process as they have led to the first non-binding consultation of 9 November 2014 and they have triggered the elections to the Catalan Parliament of 27 September 2015.

2.1.2. The Role of Organized Civil Society in Catalan's "Right to Decide"

Between 2009 and 2014, among organized civil society |32|, two independent associations were the prima facie of the bottom-up movement claiming for political independence in reaction to the moderate position assumed by the Catalan government which, at that time, was led by Artur Mas (CiU). These organizations are the Òmnium Cultural (OC) and the Catalan National Assembly (The Assemblea Nacional Catalana - ANC). These associations are now supporting the current coalition in government - Junts pel Sí (JxS) - Together for Yes - a broad single-issue coalition that reinforced the ' plebiscitary' nature of the 2015 regional election |33|.

Òmnium Cultural |34| was established in 1961 to promote the Catalan language and culture in the context of Francoist Spain. With over 65.000 members, OC is a cultural organization founded as a resistance to the dictatorship. Nowadays, it has mobilized thousands of volunteers and its aim is to expand the social majority in favor of independence. It has a national and 40 local branches, all of them ruled by elected volunteers for a period of 4 years. Public funds do not exceed 4% of the total budget and each member pays a fee which allows raising around 3 millions annually. Since 2010 it has been pushing for Catalan's right to vote their political future, and nowadays campaign for the independence of Catalonia.

In 2010, OC organized the first mass demonstration which brought together one million people against the ruling handed down by the Spanish Constitutional Tribunal against the Statute of Catalonia under the motto: "We are a nation. We decide". In 2012, the organization made a step forward and positioned in favor of the independence of Catalonia. On 29 June 2013, OC organized a concert - "Concert for Freedom" - attended by 90.000 people. Since then, it has campaigned to back the Catalan society's wish to hold a non-binding referendum in 2014, which took place in 9th November 2014. "Ara és l'hora" - now it's time - is the campaign that has been promoted by OC - a joint organization with ANC - in favor of independence.

2.1.2.2. The ANC - Catalan National Assembly

The ANC was officially founded in March 2012 after preliminary discussions starting the previous year. Its name is deliberately |35| modeled on that of the Assemblea de Catalunya, which functioned in the 1970's as a coordinating body for Catalanist opposition to the Franco regime. Existing cultural associations, and connections made during the organization of unofficial votes on independence across Catalonia from 2009 onwards, provided a ready-made pool of potential supporters. By mid-2014 it had more than 30.000 full members and 15.000 "sympathizers" (who support its work but do not pay a membership fee). The person chosen to lead the association was Carme Forcadell I Lluís, a Catalan philologist with a background in both education and language planning. In the early 1990s, Forcadell was one of the founders of the Plataforma per la Llengua, whose aim is to promote and defend the use of the Catalan wherever it is spoken. She is also a member of Òmnium Cultural mentioned before. Not only does Forcadell have many years of experience and strong networks on which to draw, but she has also become an effective symbol for the civil movement, and one of its main voices. The current president of ANC is Jordi Sanchez I Picanyol as Carme Forcadell is now the President of the Catalan Parliament.

The ANC's first major activity was to organize a massive demonstration in Barcelona on 11 September 2012, as a call for Catalonia's politicians to work immediately for independence. Although attendance figures are disputed, it is estimated that as many as 1,5 million Catalans joined the march. Mobilizing so many people through an association that had just been formed is a remarkable feat, but many of the ANC's founding members were drawn from other associations or had relevant experience in local government, the media and business. The ANC worked closely with both political parties and other civil associations, capitalizing on their existing membership and networks rather than needing to create an entirely new one of its own. After the march itself, a group of delegates was received at the Catalan parliament to make a request on behalf of the demonstrators that it should start to do whatever was necessary to achieve independence for Catalonia.

The organization of the "Catalan Way" (Via Catalana) for 11 September 2013 was even more complex than the demonstration of the previous year, since the idea was to form an unbroken human chain from the French border in the north of Valencia in the south. This would require a minimum of 400,000 participants |36|, divided between nearly 800 sections of the route. Participation was coordinated via a website, where people were asked to sign up to a particular section. Media coverage was closely coordinated by the ANC, with chosen journalists being given advance information not available to the public so that they would be in the right place to cover key surprise events on the day. In this event, the Catalan Way saw an estimated 1.6 million people taking part in the human chain and its associated activities. The culmination of the day's events was a speech given by the ANC's president, Carme Forcadell, surrounded by thousands of people in Barcelona's Plaça Catalunya. Forcadell looked tired and serious as she called for Catalonia's politicians to hold a referendum on independence without delay, saying that independence was the only way of guarantying Catalonia's future as a distinct nation. There was no triumphalism in her speech: it was heartfelt and emblematic which contrasted with the more self-interest and distant political discourse of Catalan politicians.

On May 29, 2014, the ANC, with other associations, presented at "El Born", the campaign "El País que Volem" (The Country we Want), an open participative process for citizens whose goal is to collect their proposals about how should Catalonia be when it becomes an independent state. Very seemingly, the ANC and OC organized the 2014 edition of the demonstration of the Catalan national day in Barcelona. This demonstration formed a huge Catalan flag all along 11 kilometers between Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes and Diagonal avenue forming a big "V" for will ("voluntat"), voting and victory. According to police there were 1.8 million and according to organizations 2.5 million people to demand for a poll on the 9th of November 2014.

2.1.3. Survey of Catalan Public Opinion: What does Catalonia Want?

In the late 2000's, Catalan's territorial preferences drastically changed. In 2006, Catalan independence was the first territorial preference for less than 15 % of the population |37|. At that point in time, approximately 40% of the population supported the existing system of autonomous communities, meaning that a substantial majority were not willing to make profound changes to the Spanish territorial system. The second most preferred option was to change the territorial model to turn Spain into a "federal state". Finally, the least preferred option was to turn Catalonia into a "region of Spain", in which the level of regional self-government would decrease and ultimately a new territorial system would be designed, in which the regions would have only some administrative powers.

This perception and general feeling was considerably stable until 2009. The change coincided with the series of non-binding referendums on secession that took place between 2009 and 2011, the Constitutional Tribunal release of the sentence on the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia, the deterioration of the economic situation from 2008 onwards |38| and the arrival into central government of the PP (Popular Party) at the end of 2011. During this period, the status quo and the federal options began a downward trend that only stopped at the end of 2014. In the first barometers of the Centre d'Estudies d'Opinio (CEO - Centre for Opinion Studies of the Generalitat of Catalonia) that explicitly asked about the referendum, in 2011, support for the option of independence stood somewhat above 40%. This percentage increased to above 50% from mid-2012.

In 2012, for the first time since the question was included in surveys, independence became the most preferred option. Nowadays, in 2017, 37,3% of the population believe that political independence is the best solution for Spain to the detriment for the current status quo with 28,5% and of the federal option with 21,7% (see figure 1 below). On the contrary, the choice of voting against the referendum fell from almost 30% to just above 20%, and a similar trajectory is visible in the would abstain-wouldn't vote option, which dropped from 23% to 15%.

Figure 1: "Do you think that Catalonia should be"

Source: Barometer 850, Centre d'Estudis d'Opinió (CEO), 2017

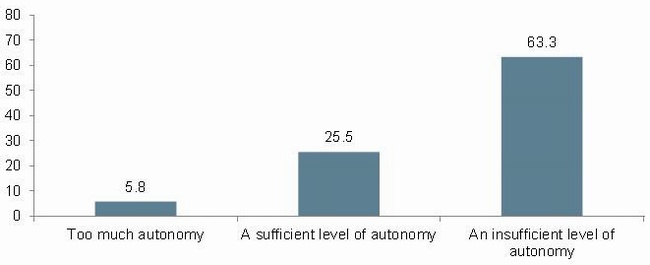

Gradually, the secessionist claim continued to attract supporters and, at the end of 2014 and 2016, it reached 45,2% |39| and 45,3% |40|, respectively, and in the last report at the beginning of 2017, it reached 44,3% |41|. In spite of nuanced variations, in early 2017, 63,3% of the population believed that Catalonia had an insufficient level of authority) - against 66,6% in 2014 and 65,6% in 2016, respectively (see figure 2 below). On top of these numbers, it is interesting to notice that on November 9 2014, 2.3 millions of people vote for independence, which represents 80% of the voters who participated to that popular consultation.

Figure 2: "Do you think that Catalonia has achieved"

Source: Barometer 850, Centre d'Estudis d'Opinió (CEO), 2017

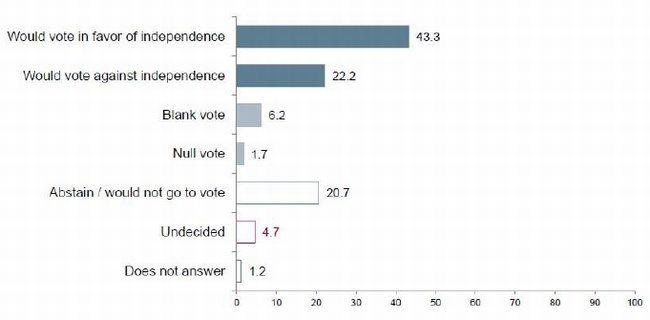

All of this data reveals that significant changes have occurred in recent years in the attitudes and opinions of many citizens of Catalonia on the territorial organization of Spain and on the institutional status of Catalonia itself. Such attitudes and opinions have evolved in a contrary way to developments in Spain over territorial organization. And among the most significant changes that have occurred in Catalonia are the increased preference for an independent State as a form of territorial organization, and the rise in the intention to vote in favor of independence in the event of a referendum vote, irrespective of whether the Spanish government wants it or not as we can see from figure n° 3 below.

Figure 3: "If tomorrow a referendum to decide the independence of Catalonia was to be held and organized by the Generalitat de Catalonia and without the agreement of the Spanish Government, what would you do?"

Source: Barometer 850, Centre d'Estudis d'Opinió (CEO), 2017

As for the question of the influence of age on support for independence, Jordi Jordi Muñoz and Raul Tormos |42| have analyzed the question by using the database of the CEO barometers as their raw material and they concluded that age has no influence on support for independence and that Catalan national identity and economic motivations held the explanation. Very seemingly, in his seminal work, Sebastià Prat |43| concluded that between 2005 and 2012, Catalan national identification played a predominant role as a factor to explain the increase in support for independence. For Prat, as in the previous case, the youngest age group of 18-34 revealed a somewhat higher level of support than older group with 58% for people between 18-34 in favor against 51% for people over the age of 64 (a difference which is not statistically significant).

From this study, it is interesting to note how the difference between the younger group and the older group, those over the age of 64, is reduced in terms of their support for independence. Very seemingly, according to these studies, we could conclude that the declared intention to vote in favor of independence is dominant in every age group, both educated under democracy and these educated under Franco and the transition to democracy. The intention among youngest group to vote in favor is 3% higher than among the total population.

Differences are much more pronounced when we cross-tabulate territorial preferences by the language usually spoken at home |44|. Among those who speak Catalan at home, 72% choose independence as their first territorial preferences |45|. The second most preferred option is the federal state with 14%. The contrast with those who speak Spanish at home is substantial. Among Spanish-speakers, the first territorial preference is the status-quo with 54%, followed by a federal state with 27%. Another variable of interest is the relationship between support for independence and the parents' geographical origins |46|.

Among Catalans with both parents born in Catalonia, support for secession is very high: it is the first preference for more than 70%. When one parent is born outside Catalonia, secession is still the first preference, but the percentage goes down to 49%. In this case, support for the federal state and the status quo slightly increases. However, when both parents are born outside Catalonia, the situation is reversed. In this case, the federal state is the preferred option for 36%, followed by the status quo with 31%. Finally, when the respondent is born outside Catalonia, the first preferred option is the status quo with 43% and the federal state with 26%. While, according to these data, it is clear that cultural identity seems an important factor to explain support for secession, it is also true that the discourse in favor of secession has largely been driven by a broader set of arguments, as we shall see later in point 5 of this chapter.

However, in spite of nuanced territorial preferences across age, language and geographical origin factors, there is a large consensus among Catalan people as for the decision to celebrate a new referendum on the 1st October 2017 with 50,5% of the respondents saying (YES) to the referendum irrespective of whether the Spanish government wants it or not; 23,3% saying (YES) but if only it is agreed with the Spanish and 22,7% saying (NO) (see figure 4 below).

Figure 4: "Are you in favor of celebrating a referendum about the independence of Catalonia?"

Source: Barometer 850, Centre d'Estudis d'Opinió (CEO), 2017